Books Reviewed

This short, loosely organized collection of occasional essays makes for a surprisingly interesting and valuable book, well worth reading and pondering. Sociologist and radical activist Todd Gitlin, who has been a figure in the American Left since his Vietnam-era days in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), has made a serious effort to reflect on the failures of the American Left since the 1960s. The criticisms he puts forward here, which are inevitably self-criticisms in part, are unsparing and penetrating, made all the more memorable by his unacademic, direct, and often epigrammatic style.

Gitlin’s criticism is relentless, and will win him few new friends on the Left, though it will likely energize the many enemies he already has there. He sees a story rich with irony, in which it has been precisely the Left’s most triumphant expressions in contemporary American life that led it into the spiritual wasteland in which it now finds itself. And for this lost condition, he believes, the Left has only itself to blame. It embraced the smug disassociation from existing society epitomized in the sweeping call by émigré philosopher and ’60s hero Herbert Marcuse for a “Great Refusal” of the confining ideals and crass manipulations of the modern capitalist political economy. But the embrace of Marcuse’s influential but ill-defined slogan has amounted in practice to a “great withdrawal,” a narcissistic retreat into self-proclaimed “marginality,” an obsession with ever more minute forms of identity politics and the infinite “problematizing” of “truth,” a reflexive opposition to America and the West, and an immurement in “theories” whose radicalism is so pure that they never quite touch down to earth—follies all underwritten and protected by the perquisites and comforts of academia.

Gitlin argues that the results may have benefited individual leftists, who have feathered their own nests quite nicely by fusing radicalism and academic careerism, but they have been unambiguously disastrous for the Left as a political force outside the academy. “If we had a manual,” Gitlin remarks, “it would be called, What is Not to Be Done.” The Great Refusal turns out to have been little more than “a shout from an ivory tower,” an advertisement of futility that was unable to conceal the despair, paralysis, and general contempt, including self-contempt, that lay behind it.

* * *

One of the many negative side effects of this Refusal has been a summary rejection of patriotic belief. There is no denying this, and Gitlin, to his credit, does not try. Indeed, this self-imposed restriction and its malign consequences are the deep subject of the book. He provides an honest account of the reasons for his generation’s disenchantment with patriotism—an account that helps explain why, even now, the term almost never escapes the lips even of mainstream liberal Democrats without being prefaced by the indignant words “impugning” and “my.” For Gitlin’s generation, the “generation for whom ‘the war’ meant Vietnam and perhaps always will,” it could be said that the “most powerful public emotion in our lives was rejecting patriotism.” Patriotism became viewed as, at best, a pretext, and at worst, an abandonment of thought itself. It became of interest only insofar as it entered into calculations of political advantage. Far from being a sentiment that one might feel with genuine warmth and intelligent affection, it was merely a talisman, which, if used at all, served chiefly to neutralize its usefulness as a weapon in the hands of others, by making it into a strictly personal preference that others were forbidden to question: “my” patriotism.

It may be that this state of affairs will continue, at least for a certain segment of Gitlin’s generation. One reason the Iraq war has been so galvanizing to that segment is that it offered badly needed reconfirmation of the very premises around which they had built their adult lives. And let it be said that those premises are not completely cockeyed. The claims of the nation-state should never be regarded as absolute and all-encompassing. To do so would violate the nature of the American experiment itself, which understands government as accountable to higher imperatives, which we express in various ways: in the language of natural rights, for example, or of “one nation under God.” The possibility of dissent against the nation for the sake of the nation is built into that formulation. The dissenters are right about that.

But by the same token, the claims of critical detachment have their limits, both practically and morally. For one thing, there needs to be a clear and responsible statement of what those higher imperatives are. And even then, the habitual resort to the ideal of dissent “against the nation for the nation” can easily become indistinguishable in practice from yet another manifestation of the Great Refusal, in which the second “nation” is a purely imaginary one to be “achieved”-and the “troops” one “supports” are entirely distinct from the actual causes for which they are risking their lives, and such “support” shows no respect for the series of conscious choices that made them into “troops” rather than civilians. When we make our commitments to one another entirely contingent, then we have made no commitments at all. There will always be reasons to hold back, always sufficient reasons to say No, if the standard against which one judges the nation is an ahistorical and abstract and imaginary one, and the only consideration in view is the purity of one’s own individual position.

* * *

For the Left, with its traditional emphasis upon fraternité, or the cultivation of human solidarity and communal values, such realities are particularly difficult to reconcile with an ethos of limitless criticism. To say that we are a part of one another—or even to acknowledge that man is by nature a “political animal,” thinking here of Aristotle and not of James Carville—is not merely to say that we should deliberate together; it is also to say that, at some point, the discussion ceases and we make a commitment to one another to act together. Furthermore, it is to say that we cannot sustain serious, demanding, and long-term commitments to one another if those commitments are regarded as provisional and easily revoked for light and transient causes. We make an agreement and we agree to stand by it. Call it a contract, a covenant, or a Constitution, it is the same general kind of commitment, a commitment not merely of the intellect but also of the will.

For any freely organized political undertaking, this vital qualification presents a difficulty. But for the Left, it becomes a profound dilemma. It is no accident, if I may put it this way, that the more attractive elements of the Left also tend to be the most schismatic and ineffectual, while the uglier ones tend to be the most disciplined and unified, in which solidarity becomes a byword for the silent obedience of the herd.

Gitlin’s generation accomplished much more than it wanted to by “demystifying” the nation and popularizing the idea that all larger solidarities are merely pseudo-communities invented and imposed by nation-building elites. By doing so, it also made “the nation” into an entity unable to command the public’s loyalty and support-and willingness to endure sacrifices—for much of anything at all, including the kind of far-reaching domestic transformations that are the Left’s most cherished aspirations. The hermeneutic of suspicion knows no boundaries, so that what is true for war—making is also true for Social Security or national health insurance. The fact is, the Left needs the nation, too, and needs it all the more in an era in which the cause of international socialism is but a faint and discredited memory. The nation is all the Left has left, whether it knows it or not.

Along with a small number of others on the left, Gitlin now recognizes this fact, and recognizes that it was a grievous error to have abandoned patriotism. His book is an effort to inch his way back toward an embrace of the national idea, without which the Left has nowhere to go, but to do so in ways that carefully avoid the embrace of “conservative” ideas of patriotism.

* * *

The abandonment of patriotism, he says, was a sure recipe for political irrelevance: how can one hope to sway an electorate toward which one has all but declared one’s comprehensive disdain? Now there is another reason. The events of 9/11 convinced him that the civilized world faces a deadly threat and that the exercise of American power in the world is not always an unmitigated evil—it may even be desirable and necessary. He was one of the many New Yorkers who flew the American flag out his window after 9/11 (though by his own admission he did not keep it up very long). He supported the invasion of Afghanistan, and sees the necessity of a continuing American struggle against the forces of jihadism.

Perhaps, he argues, there can be a “patriotic left” that stands somewhere “between Cheney and Chomsky,” here borrowing the words of Michael Tomasky, in much the same way that the anti-Communist liberals of the ’40s and ’50s stood between, say, McCarthy and Stalin. Such a Left would be critical—it being the Left’s business, in his view, to be critical—but critical “from the inside out,” always looking for possibilities for genuine improvement rather than lapsing into empty (or dangerous) gestures of condemnation. It would recognize and affirm the fact that one inevitably takes one’s stand as an American.

Such a formulation recalls the ideal—put forward some two decades ago by Michael Walzer—of “connected criticism,” which would acknowledge that no one has the ability to stand entirely outside his society or context, and that the ideal of the independent intellectual has to be balanced against the idea of intellect working within a cultural context for the common good. Gitlin’s version of this is somewhat more robust; he is even inclined to praise patriotism as a kind of “community of mutual aid,” as opposed to the sort of “symbolic displays,” “catechisms,” or “self-congratulation” that pass for patriotism. But the qualifiers are all important. Patriotism is never a blank check, and it is always undertaken with a certain provisionality and pragmatism in mind.

His formulation has many admirable aspects. For example, there is this statement: “We are free to imagine our country any way we like, but we are not free to deny that it is our country.” Or this: “It is with effort and sacrifice, not pride or praise, that citizens honor the democratic covenant.” Or his superb analysis of why what is called “community” is, in practice, often nothing more than a new form of insularity: “The crucial difference here is between a community, consisting of people crucially unlike ourselves, and a network, or ‘lifestyle enclave,’ made up of people like ourselves. Many ‘communities’ in the sense commonly overused today…are actually networks, a fact that the term disguises.” Precisely right.

* * *

But there are also troubling aspects to Gitlin’s formulations, which make one suspect that his rethinking has stopped well short of its goal. One finds far too many overtones of the past, of a patriotism that can turn on a dime and see itself as “against the nation for the nation,” and as such may not have the reliability or resiliency to withstand tribulations and crises, or the power to summon the nation to great enterprises that might be costly, difficult, and lengthy. Gitlin himself places “sacrifice” at the center of “lived patriotism,” and asserts that where there is no sacrifice (as, in his view, there has been none in the global war on terrorism as the Bush Administration has prosecuted it), there is no genuine patriotism.

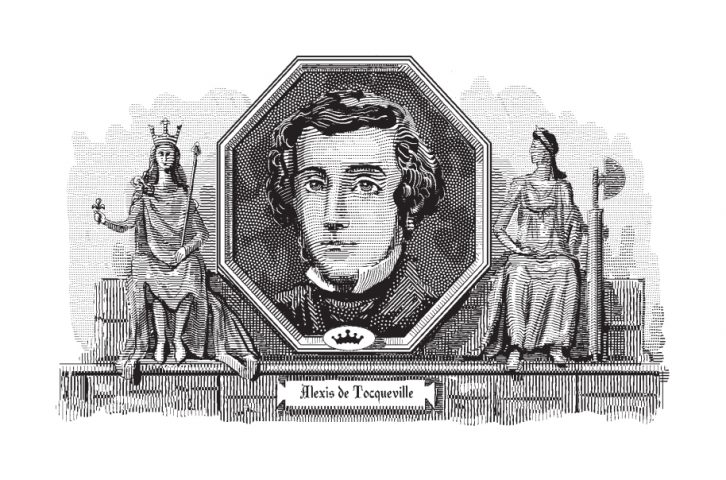

I think he is partly on target here, but only partly, for he reduces the effect to the cause. As Ernest Renan and other theorists of nationalism have insisted, the nation is constituted in large measure by the shared memories of sufferings and sacrifices past, sufferings and sacrifices that make the present generation willing to endure sufferings and sacrifices of its own—not only to keep what it has, but to keep faith with those who have come before. The role of memory is crucial; that is to say, the role of history. Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, with its invocation of the “mystic chords of memory,” or the Gettysburg Address, with its gesture toward the “honored dead” as a source of inspiration and a spirit of rededication, are paradigmatic examples of such uses of the memory of suffering. We are willing to sacrifice in part because we see that the sacrifices of those who came before us have been honored, and we too wish to be honored, as they are. But what if those who came before us cease to be honored—what then? Here Gitlin has a problem, because his view of American history is so bleak, with so few bright spots, and his contempt for the shallowness of American patriotism at present is so deep, that there hardly seems to be anything worthy of one’s sacrifice to be found in either place.

Moreover, it is not sacrifice itself, but the willingness to sacrifice for the sake of the cause of the nation, that is the crucial element in the makeup of patriotism. More than once Gitlin cites his admiration for the passengers of Flight 93 on September 11, 2001, whose airborne rebellion probably saved the White House or the Capitol building from destruction. “They hadn’t waited for authorities to define their patriotism for them,” Gitlin remarks. “They were not satisfied with symbolic displays. It dawned on me that patriotism was the sum of such acts.” Elsewhere Gitlin praises them as “activist passengers” engaging in “mutual aid.”

But this is all surely wrong, and a misappropriation of the meaning of their acts. We will never know exactly what thoughts went through their minds, but one rather doubts that the question, “What would be the genuinely patriotic thing to do?” was one of them. They did not “become” patriotic by choosing terms for their death that served the cause of the nation. No, we honor them because they were willing to act on highly imperfect knowledge, in a terrifying situation very like the fog of war, except that it was inflicted suddenly on civilians minding their own business. They behaved in ways that proved their love of country; in their willingness to sacrifice for it, they acted on a patriotism that was already in them.

* * *

There is much to like and even admire in this book, and the fact of its appearance is encouraging. But Gitlin remains, as he always has been, a man of the Left, and no one should underestimate the depth of his contempt for almost everything and everyone right of center. The book is very much in the tradition of criticism of the Left from the Left, à la Christopher Lasch and Russell Jacoby and before them Richard Hofstadter and Reinhold Niebuhr. It is written for readers who are committed to the general positions of the Left—the tacit assumption being that only the Left has ever offered anything worth criticizing, and that the Right is concerned with little more than greed and hypocrisy and the naked exercise of conscienceless power by unaccountable elites.

And yet one is almost willing to set that aside, given the usefulness of the book’s principal aim. Almost everyone, even those on the Right, ought to be able to agree with the desirability of Gitlin’s stated goal of a “new start for intellectual life on the left.” God knows we would all benefit from the emergence of a more mature, more thoughtful, more responsible, and more constructive Left than the one we have now.

But it is harder to set aside Gitlin’s unusually poisonous and quite unhinged diatribes against George W. Bush—”this lazy ne’er-do-well, this duty-shirking know-nothing who deceived and hustled his way to power,” whose rise showed that “you could drink yourself into one stupor after another, for decades and…come out on top” through “a bloodless coup d’etat”—words which are, alas, illustrative of the steep decline of public discourse that he otherwise decries. Gitlin lowers his book by not only lapsing into but luxuriating in such invective. He laments that “rarely does a fair, thorough, intelligible public debate take place on any significant political subject” in contemporary America. Too true. Yet it is hard to see how character assassination of the president contributes to rectifying this. Indeed, we see a growing decay today in the very idea of a loyal opposition—a much better term than “connected critic,” by the way, because it contains the concept of loyalty—the maintenance of which is central to the work of a civilized democracy.

The word “loyalty” itself has, like patriotism, been reduced to one of the impermissibles of discourse, conjuring as it does images of “loyalty oaths” and other constraints upon conscience and freedom of thought and expression. But there is no enduring solidarity, large or small, without loyalty, a form of commitment that endures in and out of season, and serves to lift oneself out of oneself, and acknowledges that there are imperatives and duties in life beyond the range of one’s own desires and inclinations. No one is talking about blind loyalty, and loyalty, like all virtues, has its limits. But it is an indispensable virtue, and anyone who wants to speak compellingly about patriotism cannot afford to be mute on the subject.

* * *

Gitlin has not quite come to terms with the fact-though to his credit, he does not ignore it—that this country he professes to love, or seeks to find an acceptable rationale for loving, has an alarming propensity for electing to high office people of whom he does not approve. Perhaps the first step in fostering a more genuine patriotism is being willing to take such an electorate seriously, and not to dismiss its patriotism as shallow, insubstantial, and manipulable. One might also take seriously the motives behind the soldiers, sailors, and Marines that serve the nation, men and women who most certainly make sacrifices for the common good as they understand it, and deserve at least a word or two in this book.

Still, I do not want to end on a negative note. The Intellectuals and the Flag offers penetrating, even devastating, criticisms of the intellectual state of the Left, and of the academic world that it dominates. It is a courageous book, and, with all its faults, an honest one. One hopes that it is not this talented author’s last word on the subject.