Books Reviewed

Scholarship was once considered a dispassionate vocation. The honorable scholar conducted his investigations and had little emotional stake in the findings: what mattered was telling the truth, getting it right. Now it is the scholar’s passion, his ardent parti pris, his advocacy for an outlook or a cause, the outpouring of his own vital nature, that speak loud and clear in his or her work.

The great Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897) seemed perfectly suited by temperament for a disinterested calling. He was inclined to see life in shades of gray, and actually warned scholars not to enjoy themselves unduly. Early sorrow, the death of his mother when he was 12 years old, darkened the family happiness that had warmly enfolded the boy, and the loss marked him for life, as he wrote of himself in old age in remarks to be read at his funeral: “Thus very early in life, notwithstanding an otherwise cheerful temperament, in all likelihood inherited from his mother, he received an indelible impression of the great frailty and uncertainty of all earthly things, and this determined his view of life.” Life was not to be loved incautiously or trusted very far. A hard lesson to learn at 12.

The Professor from Basel

Burckhardt’s native city of Basel, where he spent most of his life, was purse-proud and stodgy, and it gave him cause for occasional loud complaint. Hometown tedium made him long for the mental excitement and sociability of Berlin, where he had studied with Leopold von Ranke, the grandmaster of German political historiography, or for the open-air sweetness of Italy, with the lemon groves that had enchanted Goethe and the superabundance of great art. But mostly he was content in the quiet backwater. Offered the professorial chair in Berlin that Ranke had held, he turned down the honor. He never married, never really came close. Basel’s most distinguished professor, he lived alone in two rooms over a bakery.

He was a preacher’s son who lost his faith while preparing for the ministry at the University of Basel. In those days one could not be a Christian divine without believing in the divinity of Christ, but one could remain a righteous soul, and subscribe to the spirit of the Word even without accepting the letter. Ineradicable Christian decency and that inborn cheerfulness of his sustained Burckhardt. But art was his principal sustenance. He set Goethe’s poetry to music at 19; entertained company by playing the piano reduction of a Haydn or Beethoven Mass and singing all the vocal solos; frequented the opera, of which he could enjoy even “bungled” performances.

In 1869 Burckhardt welcomed to the University of Basel the newly appointed 24-year-old professor of classical philology, Friedrich Nietzsche, and during the nine years of Nietzsche’s tenure the two remarkable men enjoyed a cordial reciprocal admiration; close friendship was not in the cards, however, for Burckhardt maintained a normal appetite for “the excellent daily bread ‘good and evil,’” and Nietzsche was soon pursuing dark ecstasies far beyond the sober professorial reach. They did continue a warm correspondence after Nietzsche left, though, and it was to Burckhardt that Nietzsche wrote from Turin in the grip of madness: “I would rather be a professor from Basel than God.”

Mostly, Burckhardt worked. For him history was “poetry on the grandest scale.” The Age of Constantine the Great (1852) portrays the famously Christian Roman emperor as “essentially unreligious,” all his energies “directed to the great goal of dominion,” by way of “the streams of blood of slaughtered armies.” The Cicerone (1855), a vade mecum for art-besotted travelers, takes in just about all the Italian sculpture, architecture, and painting there is, and at a forced march, though Burckhardt lingers to swoon over Fra Angelico, Giovanni Bellini, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael. Recollections of Rubens (1897) is his testimonial to “one of the very greatest artists [who] was at the same time a perfectly luminous human being,” but here Burckhardt natters and yammers and demonstrates the unfortunate tics and crochets of an art historian of a certain era thankfully gone.

It is by three other works, however, that he is known today: the most enduring work of 19th-century historiography, Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien (1860), translated as The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy; Griechische Kulturgeschichte (posthumously published in 1898–1902), a massive edited version of university lectures he gave from 1872 to 1885, available in four volumes in German, and in a single severely abridged but invaluable English volume as The Greeks and Greek Civilization; and Weltgeschichtliche Betrachtungen (1905), put together by his nephew from lecture notes, originally translated in 1943 as Force and Freedom and later retitled Reflections on History. Burckhardt’s writings constitute the most important treatment of ancient, Renaissance, and modern history composed by one scholar.

The Renaissance

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy famously opens with a long chapter on “The State as a Work of Art,” and the strongmen Burckhardt describes are a piece of work. Frederick II, of the Norman Empire of Lower Italy and Sicily, was “the first ruler of the modern type who sat upon a throne,” and he commanded with the mailed fist of strictly centralized power. With Ezzelino da Romano, Frederick’s vicar and son-in-law, “for the first time an attempt was openly made to found a throne by wholesale murder and endless barbarities, by the adoption, in short, of any means with a view to nothing but the end pursued.” The historical devil is in the details, and Burckhardt furnishes copious diabolical details. Giovanni Maria Visconti of Milan was “famed for his dogs, which were no longer, however, used for hunting, but for tearing human bodies.” In 1409, during wartime famine, the starving Milanese gathered in the streets to cry for peace, and after Giovanni’s mercenaries had cut down 200 people from the crowd, the words pace and guerra, peace and war, were proscribed upon penalty of death, and the priests forbidden to utter the liturgical phrase dona nobis pacem, grant us peace, but required to substitute tranquillitatem. Tranquilization by terror.

Then there is Machiavelli. Burckhardt introduces him with a shudder. Writing of conspiracies ancient and modern in the Discourses on Livy, Machiavelli “classifies them with cold-blooded indifference according to their various plans and results.” Not whether the conspiracies serve good or evil, but how and whether they work, is Machiavelli’s concern, and Burckhardt is troubled. Burckhardt returns to Machiavelli again and again, as to a sore tooth he cannot leave alone. Once Burckhardt demonstrates a nearly Machiavellian understanding of Machiavelli. Considering Cesare Borgia’s connivance at the utter destruction of the Vatican power, Burckhardt intuits “the real reason of the secret sympathy with which Machiavelli treats the great criminal; from Cesare, or from nobody, could it be hoped that he ‘would draw the steel from the wound,’ in other words, annihilate the papacy—the source of all foreign interventions and of all the divisions of Italy.” But the decent professor fails to go far enough. Machiavelli would have welcomed the fall of the papacy, but his great ambition was the extinction of Christianity itself.

And when Burckhardt describes “how the doctrines of Aristotle, chiefly drawn from the Ethics and Politics—both widely diffused at an early period—became the common property of educated Italians, and how the whole method of abstract thought was governed by him,” there is not the slightest inkling how in The Prince Machiavelli demolished the Nicomachean Ethics virtually word by word and with it the vast authority of classical philosophy, and how he erected on their ruins the brutalist modern structure of brazen immorality in the service of unbridled appetite. Burckhardt’s chapter “The Revival of Antiquity” celebrates the “new civilization” whose “active representatives became influential because they knew what the ancients knew, because they tried to write as the ancients wrote, because they began to think, and soon to feel, as the ancients thought and felt.” But the foremost philosophical mind of the Renaissance was no revivalist of the ancient philosophers; defining the really new civilization, he was bent on extinguishing the ancient philosophic wisdom, and engineering what Saul Bellow called the biggest jailbreak ever. Although Burckhardt makes Machiavelli the major political figure in his history and considers him a masterly innovator of the state as work of art, he is far from comprehending how high and deep the innovation extends.

Burckhardt is more in his element when he can praise exceptionally gifted men of unexceptionable qualities. His pleasure overflows in describing the men who exercise gloriously every worthy human capacity; he rejoices as they do in the power and grace of the athletic body, the focus and sweep of the disciplined mind, the artist’s uncanny hand, the orator’s flowing eloquence, the musician’s spellbinding gravity and levity. The hero of this history is the superb being we now call the Renaissance Man. Burckhardt cannot contain himself when he encounters the very best of the best: “among these many-sided men, some who may truly be called all-sided tower above the rest.” Leon Battista Alberti, famous down the centuries as artist and architect, could perform marvels at anything he chose to do:

In all by which praise is won, Leon Battista was from his childhood the first. Of his various gymnastic feats and exercises we read with astonishment how, with his feet together, he could spring over a man’s head; how, in the cathedral, he threw a coin in the air till it was heard to ring against the distant roof; how the wildest horses trembled under him. In three things he desired to appear faultless to others, in walking, in riding, and in speaking. He learned music without a master, and yet his compositions were admired by professional judges. Under the pressure of poverty, he studied both civil and canonical law for many years, till exhaustion brought on a severe illness. In his twenty-fourth year, finding his memory for words weakened, but his sense of facts unimpaired, he set to work at physics and mathematics.

The catalogue of wonders goes on for another full page; Burckhardt, and the awestruck reader, cannot get enough. “It need not be added that an iron will pervaded and sustained his whole personality; like all the great men of the Renaissance, he said, ‘Men can do all things if they will.’” Alberti’s byword might stand as the epigraph to every history of the Italian Renaissance ever written.

And surpassing even Alberti was Leonardo da Vinci, “as the master to the dilettante.” Leonardo was so extraordinary that Burckhardt encapsulates his incomparable excellence in but three brief sentences, for “[t]he colossal outlines of Leonardo’s nature can never be more than dimly and distantly conceived.” True perhaps, yet to memorialize such a man is plainly the work that brings Burckhardt the fullest happiness, and one wishes he had said more and more on this supreme master.

Burckhardt feels bound to devote page after page, however, not only to the liberation of life-enhancing energies for the newly free individual, but also to the loosing of demonic forces that were the black aspect of the new individuality. There are after all sides to many if not most individuals better left undeveloped, Burckhardt ruefully admits. The final chapter, “Morality and Religion,” details the era’s considerable traffic in immorality and irreligion. Too many humanists proved all too human; sexually profligate, avaricious, obsessed with rank and comfort, men without qualities or beyond good and evil, they brought disgrace upon the vocation that had promised a new epoch of benevolent wisdom.

“The restraints of which men were conscious were but few. Each individual, even among the lowest of the people, felt himself inwardly emancipated from the control of the state and its police, whose title to respect was illegitimate, and itself founded on violence; and no man believed any longer in the justice of the law.” Murderers who faced the hangman with bold indifference inspired public admiration. Paid assassins, small-scale condottieri, never wanted for business. The more intense the sense of one’s individual significance, the more inconsequent and even spectral the other lives that got in one’s way.

And yet: “By the side of profound corruption appeared human personalities of the noblest harmony, and an artistic splendor which shed upon the life of man a luster which neither antiquity nor medievalism either could or would bestow upon it.”

The Greeks

It is Greek antiquity, however, and most especially the period of Athenian democracy, that is still sometimes seen, and was emphatically seen in Burckhardt’s day, as the acme of human flourishing: of peerless beauty, excellence, happiness; physical, intellectual, artistic, political. But Burckhardt mounts quite a case to the contrary in The Greeks and Greek Civilization, portraying the terrible price the Greeks paid for their achievement, and the fatal erosion of that achievement by self-destructive currents amounting to mass insanity.

The transports with which the German neo-humanists exalted the Greeks shaped German self-perception as the nation formed itself throughout the 19th century; the modern German love for ancient Greek ways proved that Germans were the next best things to Greeks ever and unquestionably the finest people of their own time. The art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann set the terms and the tone of this admiration. In the booklet Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755), Winckelmann declares,

The general and most distinctive characteristics of the Greek masterpieces are, finally, a noble simplicity and quiet grandeur, both in posture and expression. Just as the depths of the sea always remain calm however much the surface may rage, so does the expression of the figures of the Greeks reveal a great and composed soul even in the midst of passion.

To be capable of rendering such grandeur, the Greek artist had to be a man of sterling magnanimity himself; such artists were philosophers, Winckelmann avers, whose wisdom spoke in their touch.

In the long essay “Winckelmann and His Age” (1805), Goethe hails the path-breaking and trend-setting critic as “the reincarnation of ancient man—insofar as that may be said of anyone in our time.” Taught to see and to feel by Winckelmann and his Greeks, Goethe expounds the ultimate humanist optimism, for which the beautiful and joyous human being is the pinnacle of Creation.

When man’s nature functions soundly as a whole, when he feels that the world of which he is part is a huge, beautiful, admirable and worthy whole, when this harmony gives him pure and uninhibited delight, then the universe, if it were capable of emotion, would rejoice at having reached its goal and admire the crowning glory of its own evolution.

This is what it meant to be a Greek, and what it means to be the inheritor of the Greek legacy, like Winckelmann or Goethe. At its highest, Greek art proffers intimations of human divinity. In the Olympian Zeus, by Phidias from the 5th century B.C.—a lost sculpture that Goethe had only read about—“A god had become man in order to make man into a god. [The Greeks] saw supreme majesty and were inspired by supreme beauty.” The work of a serious modern soul is to make oneself, as Winckelmann had, “receptive to such beauty,” and consequently happy beyond the reach of sooty gray modernity.

So proclaims the neo-humanist tradition in which Burckhardt was schooled, but in his caustic reappraisal, such loose talk of the Greeks’ world as a “beautiful, admirable, worthy whole,” radiating endless delight, could not be more mistaken. In fact, Burckhardt makes his case, Greek culture was shot through with the terror of life, shaken by social disorder, ferociously competitive yet joyless in the striving, riddled with malicious envy of outstanding men, overseen by gods whose power only fortified their immorality and outright wickedness, and given to an unsparing lucidity that made dying seem the happy alternative to living in such misery.

He begins with the esteemed place that criminal horror occupied in the mythos: “the fathers who killed their daughters, the mothers who killed their sons, the marital murders, suicides, murders of relatives and so on, with three examples of those whose own children were served up for them to feast on.” And the gods were more cruel than men. The pathos of beauty overwhelmed the pleasure to be taken in its flowering. It was a life in which everything they clung to could be lost. Greek military law mandated the destruction of the vanquished city: “the execution of the men, the enslavement of women and children, so that of countless Greek cities nothing but a heap of ruins remained. For those who experienced it, the transition from a life they had lived in its utmost intensity to this total annihilation must have entailed appalling human misery and rage.”

The Greeks did not require the torturous intellectual apparatus of 19th-century nihilism in order to fear and hate their lives: they simply had to live them. Burckhardt finds literary authority in abundance on fundamental human wretchedness. Herodotus is full of the ineradicable sadness of existence. Priority is disputed for Sophocles’ famous declaration that “not to be born is best”; many before him knew it and said so, and the relevant collection of anecdotes “amount[s] almost to an anthology of Greek pessimism.”

Suicide was the easiest way out, and chosen often on “slight provocations.” ‘“Only a coward or a fool,’ says Sophocles, ‘will cling to life in misfortune.’” Excessive love of life was condemned as cowardice; servants and slaves were especially prone to such ignominy, which free men despised. Of the 11 pages Burckhardt devotes to suicide, half describe mass suicides as the prudent alternative to being slaughtered or enslaved by a triumphant enemy.

Burckhardt determined the Greek polis to be a pathological phenomenon, penetrating every thought and feeling of a citizen’s life, more intrusive and oppressive than modern tyranny. In his monumental History of the Art of Antiquity (1764), Winckelmann had written, “With regard to the constitution and government of Greece, freedom was the chief reason for their art’s superiority…. Through freedom, the way of thinking of an entire people sprang up like a fine branch from a healthy trunk.” Burckhardt pronounces the entire growth rotten, with unfreedom at the root. The Greek political arrangements were utterly inimical to the thinking of modern men, who value the state insofar as it assures their personal freedom. The polis consumed the individual. It was for the sake of the polis that every citizen lived, and there was no escaping its control.

Internally, the polis was implacable toward any individual who ceased to be totally absorbed in it. Its sanctions, often put into practice, were death, loss of civic rights, and exile…. The absence of individual freedom went hand in hand with the omnipotence of the State.

The Athenian democracy, vaunted citadel of freedom and individuality, was most pernicious of all. “Although this enslavement of the individual to the State existed under all constitutions, it must have been at its most oppressive under democracy, where the most villainous men, ridden by ambition, identified themselves with the polis and its interests and could therefore interpret in their own way the maxim salus reipublicae suprema lex esto (‘let the safety of the Republic be the highest law’).” The law of the polis was instinct with mythic authority, so that “fundamentally the polis was [the Greeks’] religion,” and a hard faith it was.

Modernity

Yet if Burckhardt was the most severe critic going of ancient unfreedom, he detested even more what the men of his time were doing with their unexampled freedom. His correspondence seethes with loathing for the multitudes on the rise and the politicians and intellectuals who service them. To his mind, proles, petit-bourgeois, and their paladins alike make up the insufferable masses. Republicanism offers the illusion of progress and freedom, while it condemns a once rich culture to spiritual destitution.

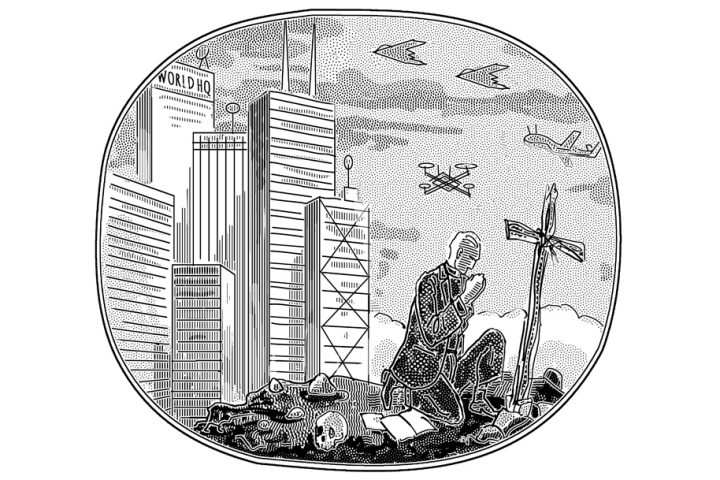

His passionate animadversions against modernity spill over into the university lectures collected as Reflections on History. He deplores “the modern centralized state, dominating and determining culture, worshipped as a god and ruling like a sultan.” Like Alexis de Tocqueville, Burckhardt sees centralized power advancing in lockstep with equality, and even more acutely than Tocqueville he fears that these conjoined forces will drive what remains of true freedom and individuality to the wall. This omnipotent state is the proving ground for the latest ideas of what humanity ought to be, with “the most turbulent individuals demanding the most extreme control of the individual and the community.” As the masses demand more and more of the state, expecting it to fulfill their ever burgeoning desires, they plunge it into debt it can never climb out of—“the chief, miserable folly of the nineteenth century.”

Burckhardt lays waste the confidence in progress of both the Hegelian philosophy of history and the Whig interpretation of history that celebrate it.

Our profound and utterly ridiculous self-seeking first regards those times as happy which are in some way akin to our nature. Further, it considers such past forces and individuals as praiseworthy on whose work our present existence and relative welfare are based. Just as if the world and its history had existed merely for our sakes! For everyone regards all times as fulfilled in his own, and cannot see his own as one of many passing waves.

Ranke had deemed all ages equidistant from eternity; Burckhardt sees them all equally remote from happiness, a word he wishes to banish from “the life of nations,” while retaining for the historian the very useful and apposite word unhappiness.

To search the world’s unhappiness to the bottom is the historian’s task, and such work is the closest thing to happiness he will know—though it is best even here not to speak of such a thing as happiness. For “life, as it becomes self-conscious in and through history, cannot fail in time so to fascinate the gaze of the thinking man, and the study of it so to engage his power, that the ideas of fortune and misfortune inevitably fade…. Instead of happiness, the able mind will, nolens volens, take knowledge as its goal.” Sublime disinterestedness, then, is the purest passion. The historian’s ideal, and such happiness as he enjoys, is very like the Greek philosopher’s, like Aristotle’s in particular. How far Jacob Burckhardt upheld that ideal is a question that historians and political men will continue to dispute in time to come, for his is a mind that matters, in its passion and dispassion.