An old man, long held captive in a nightmarish prison, stays alive by killing weaker prisoners, including his own son. When asked how he can do such a thing, he says that he does it for food, because “Real hunger is when one man regards another man as something to eat.” In the same hellish place, a group of prisoners are lined up and shot in the head. As they fall into the ditch prepared for their bodies, other prisoners clamber down and grab the shattered skulls, because as one later explains, “Human brains are, in fact, so tender you can eat them absolutely raw.”

If I told you these ghastly scenes were from the latest episode of The Walking Dead, you would have reason to believe me. Now entering its seventh season on the AMC channel, The Walking Dead is adapted from an eponymous comic book about a “zombie apocalypse” and has the highest Nielsen ratings of any cable TV series in history. It may also have the most graphic violence. The zombies, or “walkers” as they’re called, are humans who have died from a mysterious plague that, after killing its victims, revives them as mindless predators ravenous for living human flesh.

Every episode of The Walking Dead contains at least two walker attacks, in which the lurching, rasping, slavering walkers pursue the small number of humans who have survived the plague. When the humans are caught, we are treated to the hideous sight (and sound) of the walkers greedily consuming their bodies. When the humans fight back, we are regaled by the equally hideous but presumably more reassuring spectacle of walkers being destroyed en masse. Enhancing the horror is the walkers’ elaborate makeup, which makes them look like decaying corpses.

As it happens, the ghastly scenes I began with do not come from The Walking Dead. Instead, they come from a collection of short stories about Auschwitz by the Polish poet Tadeusz Borowski. Arrested by the Gestapo in the winter of 1943, Borowski spent two years in the death camp—where as a young, non-Jewish male he was made a Vorarbeiter, or low-level functionary performing grim tasks like seizing the belongings of arriving Jews, and removing dead infants from the vacated railway boxcars.

This middling position, below the hated kapos but above the doomed multitude, makes Borowski’s posthumously published book, This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen (1959), uniquely chilling. As Czes?aw Mi?osz expressed it: “In the abundant literature of atrocity of the 20th century, one rarely finds an account written from the point of view of an accessory to the crime.”

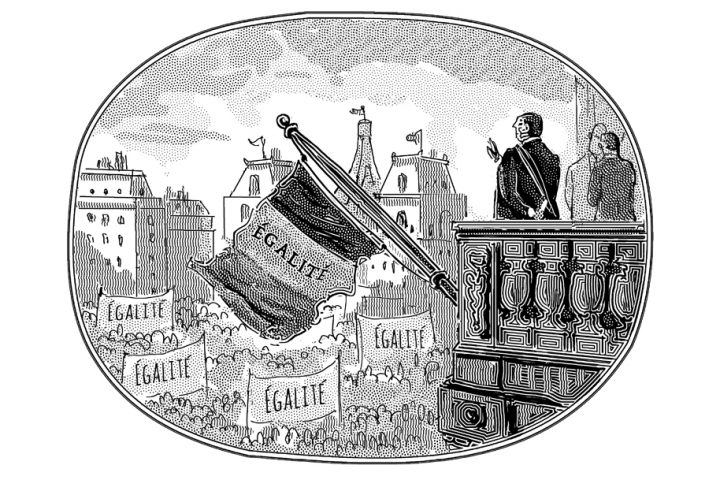

After the war, Borowski returned to Poland, married his fiancée (who had also been in Auschwitz), and saw his work briefly celebrated by the new Communist regime. But then Stalin handed down his diktat that the death camps be portrayed in black-and-white terms as an ideological struggle between heroic Communists and villainous fascists. Outwardly conforming, Borowski churned out reams of hack literature, hack journalism, and made-to-measure propaganda. But inwardly, his only remaining reason for living—in his words, “to grasp the true significance of the events, things, and people I have seen”—was collapsing under the pressure. In 1951, at the age of 28, he committed suicide.

Fear of Breakdown

It may seem a stretch—okay, it is a stretch—to compare a classic of Holocaust literature with a cable TV show about zombies. But the comparison is apt in one sense: like Borowski, the creators of The Walking Dead tried in the beginning to tell their horror story in a way that was honest and true. And they succeeded, only to see their success appropriated by a powerful authority with a heavy investment in telling the story in a way that was meretricious and false.

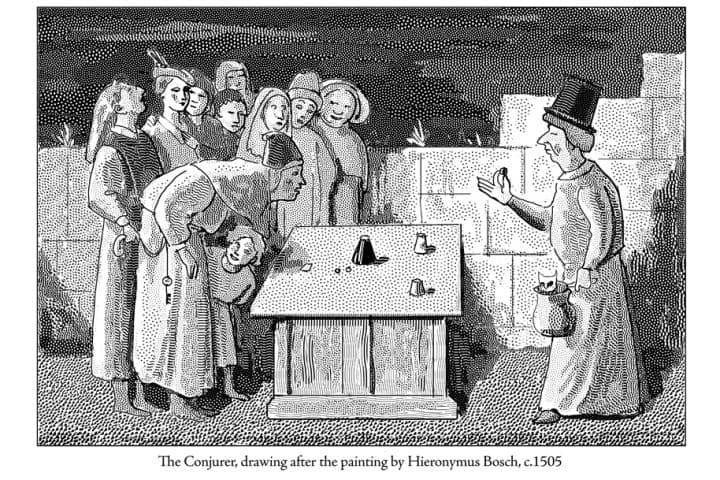

In the vodou religion of Haiti, a zombie is a living person who is rendered cataleptic by a powerful poison, buried as though dead, and then revived to become the soulless slave of an evil sorcerer. After the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804, in which vodou played a significant role, the zombie became a symbol of slave revolt and racial “pollution” in North American folklore, fiction, and later film. Today’s zombies are more likely to be caused by science than by sorcery, and the negative racial symbolism has faded. So the question becomes: what do zombies symbolize today?

The easy answer is “creepy people who are not like us.” A more intriguing reply comes from Steve Zani and Kevin Meaux, literature professors at Lamar University. In an essay comparing today’s “zombie narratives” with the plague narratives of medieval and modern Europe, Zani and Meaux argue that both evoke a primal fear “that the institutions holding our culture together, often specifically law, family, and belief in the sacred, will break down or reveal themselves to be false in the face of catastrophe…. [I]t isn’t the specifics of an individual breakdown that are essential, but rather the very idea of breakdown, the dissolution of certainty and meaning.”

In 2010, when The Walking Dead premiered, Americans were feeling, if not primal fear, then a deep current of anxiety arising from the financial crisis; the faltering of U.S. military and diplomatic interventions in the Middle East; the Wikileaks dumping of classified information; and a slew of festering problems long ignored by our political elites: depressed wages, joblessness, uncontrolled immigration, drug addiction, loss of community, family breakdown, and cultural debasement. When The Walking Dead became a hit, it was partly because (like certain other “hits” in popular culture) it resonated with the public mood without attempting to address any particular issues.

During its first two seasons, some hardcore fans faulted The Walking Dead for focusing too much on the “soap opera,” by which they meant the relationships among the human characters. This makes sense if one’s taste is limited to horror movies and ultraviolent videogames. But to anyone whose taste extends a bit further, there is nothing soap-operatic about the drama that unfolds over those first two seasons.

The pilot episode, “Days Gone Bye,” opens with Rick Grimes (played by Andrew Lincoln), a sheriff’s deputy in King County, Georgia, lying in a coma caused by a gunshot wound received in the line of duty. Emerging from the coma, Rick finds himself in a world transformed by an unknown but catastrophic plague. As he begins to explore his surroundings, we see in quick succession a hospital that is no longer a hospital, a town that is no longer a town, and—worst of all—people who are no longer people.

Pursued by ravenous walkers, Rick is eventually rescued by Morgan Jones (Lennie James), a father barricaded with his young son in their home. There Rick regains enough strength to set off for Atlanta in search of his wife, Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies), and son, Carl (Chandler Riggs). After Rick leaves, we get a foretaste of what is to come. Retreating to the attic, Morgan gazes at a photograph of his wife, then takes a gun and begins to shoot walkers outside in the street. The noise attracts more walkers, including his dead wife. He aims at her, but although she is clearly a zombie who would eat her own son if she could, he cannot bring himself to pull the trigger.

Ethical Scruples vs. Killer Instincts

Over the course of Season 1, Rick reunites with his family and becomes the leader of a small band of human survivors that also includes Shane (Jon Bernthal), a boyhood friend who was also a sheriff’s deputy serving as Rick’s partner. Season 2 opens with the band being given refuge on an isolated farm by its owner, an elderly veterinarian named Hershel (Scott Wilson). Rick and Lori use this respite to mend their frayed marriage. Lori ends the affair she began with Shane when they both believed the comatose Rick was dying. And a troubled widow named Carol (Melissa McBride) keeps searching for her young daughter, Sophia, who ran off during a walker attack.

This is the setting for “Pretty Much Dead Already,” the extraordinary seventh episode of Season 2, which begins with the realization that Hershel, the veterinarian who owns the farm, is a kind-hearted Christian who wants to believe that the walkers can be cured. So he has been harboring a score of them—including family members and neighbors—in his barn. Not only that, but Hershel has been making forays into a nearby swamp to rescue walkers stuck in the mud and, capturing them with snare poles, leading them to safety in his barn.

Hershel’s scheme is madness, because the only cure for the walkers’ condition is swift destruction of their brains. Rick knows this, but he goes along out of gratitude for the refuge Hershel has provided—and, it seems, out of gladness at learning Lori is pregnant. Shane’s reaction is the opposite. Unlike Rick, who is high-minded and rational, Shane’s instinct is to shoot first and ask questions later. Shane is also feeling humiliated by Lori, who in addition to rejecting his advances has just told him that, even if he is the father of her baby, the baby will be raised by Rick.

What happens next is stunning. Shane summons all the survivors to the barnyard and gives them weapons, telling them that they must do what is necessary. Then he throws open the barn doors. Out stagger the walkers, leaving the survivors no choice but to start shooting. This is the first time we see the humans deliberately exterminating the walkers. Hershel collapses at the sight of his family members and neighbors being mowed down. And when the carnage is almost complete, the last walker to emerge is Carol’s lost daughter, Sophia. Everyone stands paralyzed until Rick asserts his leadership by stepping forward and shooting the girl.

Throughout this scene, there is a palpable sense of a once-solid moral universe dissolving. Rick and Shane continue to clash for the rest of Season 2, and in the penultimate episode, Rick finds it necessary to kill his old friend and partner. But the act brings scant relief, because by then the line between ethical scruples and killer instincts has become blurred in a way that resonates profoundly with the unease many Americans are feeling—not only about our safety in a hostile and turbulent world, but also about our sanity.

The Joy of Shooting

If The Walking Dead were a novel, play, or film, Shane’s death would be the denouement, leading either to demoralization and defeat, or to some kind of stoic acceptance of terrible necessity. But here we see the difference between a coherent drama with a beginning, middle, and end, and an open-ended, moneymaking franchise. Having conjured the worrisome national mood, the higher-ups at AMC saw no reason to wrestle with it. Instead, they fired Frank Darabont, the veteran filmmaker best known for The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, who had developed the series. And, like Stalin dictating what writers must say about Auschwitz (another stretch, I admit), they imposed a formula to grow the franchise.

The formula goes like this: Wandering the post-apocalyptic wilderness, the good human survivors—the heroes—fend off the walkers long enough to reach a potential sanctuary, where after a brief respite they are attacked by bad human survivors—the villains—who, being human, are much more interesting than the walkers. There follows a terrible battle, which the heroes win, but at the cost of being once again cast into the post-apocalyptic wilderness.

Rinse and repeat. With each passing season the violence, and the villains, become more extreme. But The Walking Dead does not become any better, because although the human drama has not disappeared altogether, it now takes second place to the formula, which consists of two highly marketable ingredients. The first is the continual, guilt-free killing of the walkers, who are now so thoroughly dehumanized, the humans think nothing of blowing them away. On occasion, even the most heroic survivors seem to derive pleasure from these orgies of mass killing.

This is, of course, very similar to the pleasure derived from violent first-person-shooter videogames, including quite a few with “Walking Dead” in the title. It is frequently argued that this form of entertainment provides a harmless outlet for aggressive impulses, especially in young males. But having seen how material from these games is used in the recruitment efforts of ISIS and other terrorist and criminal gangs, I would suggest that the jury is still out on this question.

The second marketable ingredient is the elimination of moral complexity in the human characters. In a 2012 interview, Jon Bernthal, the actor who played Shane, commented that when Darabont was developing the series, the idea was to have

[no] good guys and bad guys, no “heroes and villains.” We were really trying to make this as authentic and real a piece as we could. I think that’s what the draw is. It’s a zombie show, but we are not doing it in a campy way, we’re not winking at the audience. We’re playing it for real.

Season 3 introduced the first unalloyed human villain, a would-be tyrant called “the Governor.” Since then, the human villains have become increasingly important to the plot—and, as noted earlier, increasingly extreme and grotesque. In keeping with the general drift of American popular culture, the writers and producers seem to be lavishing far more imagination and creativity on the bad guys than on the good.

For example, Season 4 ends with the good human survivors, still led by Rick, arriving at a potential sanctuary called Terminus—only to be locked in a railway boxcar by their hosts, who turn out to be bad human survivors who practice cannibalism. Early in Season 5 there is a scene in which Gareth, the cannibal leader, is shown taunting one of the captives, a member of Rick’s band called Bob, while at the same time chewing on Bob’s severed leg, which is being roasted over a fire. As Bob writhes in mental and physical agony, Gareth delivers what is supposed to be a laugh line: “If it makes you feel any better, you taste much better than we thought you would.”

Are you laughing, innocent reader? I confess to a grim smile. But consider: are we so secure in America right now, both from our enemies and from ourselves, that we can smile and wink at a popular culture saturated with scenes of depravity that could have been taken from Auschwitz? There was a time, not long ago, when such depictions would have been judged too disturbing to show in a public theater, much less stream to billions of televisions, computers, and handheld devices around the world. That time is past, and our media have entered a whole new era. Is it an era of sophisticated, liberated expression? Or does it portend a plague?