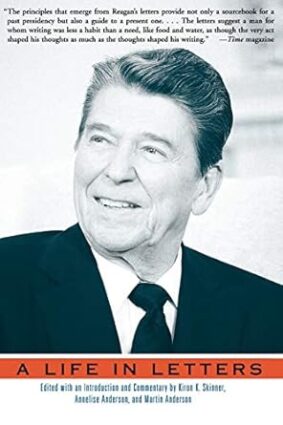

Books Reviewed

On my first visit to Washington, D.C., as an undergraduate many years ago, I asked a congressman how much of his constituents’ mail he read. His answer stunned me: “As little as possible.” So much for my youthful image of our representatives keeping in close touch with The People.

So it is all the more extraordinary that Ronald Reagan not only insisted on regularly reading a large sample of mail sent to the White House, but that he spent hundreds of hours writing replies to ordinary and distinguished citizens alike. The civil servants in the White House post office raised the alarm a few days into Reagan’s first term that someone was using the President’s special stationery to send out letters. They couldn’t believe it was the President himself. But Reagan hand-wrote an estimated 1,000 letters during his presidency—many of them written during the period in the afternoon blocked out in his schedule as “personal time,” when everyone in Washington assumed that he was taking a nap. As was so often the case with Reagan, it was the conventional wisdom that was asleep.

Following on Reagan, in His Own Hand, their selection of radio addresses composed by Reagan himself, Kiron Skinner, Annelise Anderson, and Martin Anderson have culled the best from 5,000 handwritten drafts of the more than 10,000 letters Reagan is estimated to have written in his lifetime. Reagan began his letter-writing habits during his Hollywood days, when he thought it important, as well as necessary for his film career, to reply to his fan mail. He kept up this practice as he began his long transition into a person of political substance.

The sheer repetition that appears in these letters will give ammunition to Reagan’s admirers and critics alike. His admirers will delight in seeing the constancy and firmness of his opinions across the years against withering pressure to yield, while his critics will see his repetition of familiar themes and factoids as confirmation of his supposed simple-mindedness. In parsing Reagan’s arguments, though, both admirers and critics may overlook the massive fact of Reagan’s remarkable sincerity and doggedness. He never tired of writing out again and again the same arguments and sentiments, as though he were expressing them for the first time. An ordinary politician would have resorted early on to scribbling a code for the appropriate form-letter response.

But the man we know as “the Great Communicator” thought it his duty—as well as within his capacity—to persuade every American, one at a time if necessary, of his point of view. Here and there, the reader finds clues that explain this extraordinary need to connect with citizens one-on-one. In a long letter written to a stranger who had complained during the 1980 campaign about a form letter from the Republican National Committee, Reagan wrote: “I don’t think of voters as voters. They are people.” This may help to explain and demystify one of Reagan’s most oft-mentioned traits—his lack of close friends. This supposed “remoteness” has been overstated and wrongly drawn. If Reagan seemed to lack intimate friends, it may be because he thought every American could be his friend.

While the most obvious aspects of his letters are his conviction and his humor, there do appear small signs of dimensions to Reagan that outside observers could only intuit. For one thing, he shows remarkable judgment about other politicians. In June 1979, during intrigue over whether Senator Ted Kennedy (whom Reagan refers to in a 1986 letter as “that playboy from Massachusetts”) would challenge President Carter for the Democratic nomination in 1980, Reagan wrote: “I must say that Senator Kennedy does remain an enigma in the coming race. I find myself believing that he truly would like to stay out of this race, waiting for 1984, but he may be pushed into it if things continue to worsen for this president.” Reagan’s insight into Kennedy’s reluctance was right on the mark; Kennedy ran a feckless campaign. Reagan was equally perceptive about the prospects of Jack Kemp running for president in 1980, writing in a February 1979 letter: “My own hunch is that Jack will stew and stew and then maybe not even try for the Senate but just stay in that nice safe spot he has. Maybe it was football, but he does play the percentages.”

* * *

The letters also offer examples of a toughness, discipline, and canniness that his public geniality masked. As is well-known, Reagan wrote several personal letters to Soviet leaders, starting with Brezhnev in 1981 while Reagan was recuperating from the assassination attempt. These letters expressed his sincere goodwill and desire for peace, though many conservatives thought them naive or even frivolous. But to a navy admiral Reagan wrote in 1983: “I have never believed in any negotiation with the Soviets [in which] we could appeal to them as we would to people like ourselves.” The key is Reagan’s tacit distinction between talking to the Soviets as people and negotiating with the Soviets as an adversary. His succinct outline of strategy and policy displays a keen understanding of political skill: “Negotiations with the Soviets is really a case of presenting a choice in which they face alternatives they must consider on the basis of cost. For example in our arms reductions talks they must recognize that failure to meet us on some mutually agreeable level will result in an arms race in which they know they cannot maintain superiority. They must choose between reduced, equal levels or inferiority.” Nothing sentimental here about mutual desires for peace.

Reagan: A Life in Letters sheds new light on several key moments in Reagan’s long political odyssey, such as the role of the brilliant but troublesome John Sears, the manager of Reagan’s 1976 campaign whom Reagan fired early in 1980. Many conservatives distrusted Sears, and voiced this distrust to Reagan. Sears never perceived his own potential vulnerability, which Reagan indicated in a February 1979 letter to New Hampshire newspaper publisher William Loeb roughly a year before Sears’s climactic firing: “Let me just respond to one thing about John Sears. We are all well aware of his shortcomings as well as his talents and know that last time we gave him the ball without very much of a game plan. It’s going to be very much different; he will be part of the organization. But the head man is definitely going to be Paul Laxalt, and John will be doing those things we think he does well, but not a solo job with all of us wondering what happened next.” When Sears went increasingly solo as the 1980 campaign began to unfold, Reagan showed him the door.

* * *

It is possible to see in Reagan’s generosity and good-heartedness toward his critics the same innocent disposition that couldn’t believe any of his senior staffers could be working against him. Numerous letters blame the media for accounts that the White House was split between the ideologues and the pragmatists, as in 1984 when Reagan says “the media has exaggerated supposed differences within our administration. It is true I encourage presentation of all facets but there is no compromise with principle on my part nor has such been urged upon me.” In another letter from 1984 Reagan declared, “I’m not being manipulated by people who are out to change my beliefs. If there were any such trying I’d kick their fannies out of here.” Here one must wonder whether deference shown in front of the President didn’t obscure Reagan’s own perception of the severe infighting going on outside the Oval Office—most notably in the attempts to get him to reverse course on his income tax cuts. Reagan successfully resisted the worst of this, which may be one reason why he could downplay in his own mind the splits that did exist. He never doubted that he was in control.

Reagan knew who his real political enemies were: the media, and especially the “eastern establishment.” “My cabinet will not be composed of members of the eastern establishment,” he wrote in 1980. The media, he rightly perceived, was part of what he often described as “our permanent lynch mob” in Washington, who are “less interested in legitimate news than they are in proving their knowledge and wisdom is superior [to] ours.” “In my nightly prayers,” he wrote to William Rusher in 1984, “I have to ask forgiveness for what I’ve been thinking about those villains all day. It’s not an easy thing to do.”

In addition to fueling our speculations about Reagan’s possible misperceptions, his letters allow us an opening on his mistakes. He defended to several skeptics his nomination of Sandra Day O’Connor to the Supreme Court, writing in 1981 to Harold O.J. Brown that “[s]he has assured me that she finds abortion personally abhorrent. She has also told me she believes the subject is one that is a proper subject for legislation.” There are also some letters where Reagan can be seen contriving explanations. For example, in 1985 he writes that “the first time I ever thought of seeking the presidency was in 1976 because I thought Jerry Ford could not beat Jimmy Carter whom I’d known as a governor.” This can’t be right. At the time Reagan geared up to challenge Ford in the fall of 1975, Carter was still a dark horse candidate in single digits in the polls. Witnesses at the time recall that Reagan thought Ford a weak leader who would lose to any Democrat. Why not say this in 1985? Perhaps Reagan, who had come to have some fondness for Ford, wished to circumscribe his previous contempt, even if expressed only in a private letter.

There is much more to be pondered in Reagan’s letters, including his religious piety, his shrewd mix of practicality with ideological conviction, and his nuanced view of government. “President Lincoln said it is possible to be loyal to government and still be critical of those in power. You will never hear me assail our system or the Constitution,” he wrote in 1977. In other words, Reagan was not the simple anti-government libertarian he is sometimes described as being. He showed a grasp of the real problem when he wrote in 1979, “The permanent structure of our government with its power to pass regulations has eroded if not in effect repealed portions of our Constitution.”

One fervently hopes that the next installment in the project of uncovering Reagan’s mind will be the publication of excerpts from the diaries he dictated and scribbled down during his presidency. The diaries have largely been dismissed as mere chronology and recollections of the dinner seating arrangements (so said the clueless Edmund Morris). Yet the treatment of Ford in the aforementioned letter suggests the possibility of a much greater subtlety to Reagan’s mind. The diaries almost surely include some gems for those willing to dig carefully.