Books Reviewed

Twenty years ago, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) was hailed by its supporters as the final resolution of the illegal immigration problem. It gave a “one-time only” amnesty to nearly 3 million illegal aliens living in the United States, promised increased border security, and enacted criminal penalties on employers who knowingly hired illegals. In the end, the enforcement provisions were never taken seriously and the amnesty provisions, as many predicted, gave a new incentive to illegal immigration, fueling the hope (perhaps even the expectation) that amnesty was merely the precursor to a series of ever more generous offers.

Today, the United States is mired in a deeply divisive debate about immigration, again brought on by the intractable problem of illegal immigration. The fact that there are more than 11 million illegal aliens currently in the U.S. is clear evidence of IRCA’s failure—or perhaps its success! After all, immigration policy is mostly an inside-the-Beltway affair, where constituencies seeking to boost immigration—including illegal immigration—abound. Immigrant rights groups, business interests, labor unions, and various ethnic advocacy groups all have a stake in the debate, hoping to magnify and extend the reach of their power by increasing immigration at all costs. Indeed, the administrative state itself has an interest in increasing immigration, especially from the Third World and other undeveloped nations. These immigrants, legal and illegal, often become malleable clients of the welfare state.

Semantics aside, the Bush Administration wants amnesty to be the centerpiece of any new immigration bill. The president believes that illegals are only seeking to improve their lives, and so he has called for greater “compassion for our neighbors to the south” because “family values do not stop at the border.” By becoming a more “welcoming” society, he claims, we will become a “more decent” people. Of course, any new proposal will contain provisions to strengthen border security and impose sanctions against recalcitrant employers. The IRCA had similar provisions; and amnesty is certain to set off another wave of illegal immigration. Even the prospect of amnesty has already produced a new surge of border-crossers.

One important aspect of immigration policy that is conspicuously absent from the current debate is whether immigrants should be expected to adapt to an American way of life, including exclusive allegiance to the Constitution and its principles. Liberal opinion, of course, maintains that the idea of sovereignty is anachronistic in an increasingly globalized world; human dignity inheres in the individual, and should not require the mediation of the nation-state. In fact, multiculturalism, we are told, is a necessary consequence of the respect for human dignity, and any demands made on behalf of the nation-state for exclusive allegiance or for assimilation are contrary to respect for “universal personhood.” By this logic, liberal democracy’s worldwide advance will soon render citizenship, itself, superfluous.

* * *

With his new book, True Faith and Allegiance, Noah Pickus has undertaken an ambitious and altogether praiseworthy project that attempts to articulate a coherent ground for both citizenship and assimilation in a world characterized by “competing subnational and transnational forces.” The Associate Director of Duke University’s Kenan Institute for Ethics, Pickus characterizes “the essence” of his book as a “difficult dialectic between maintaining the bonds of nationhood and allowing them to be flexible enough to include newcomers.” This dialectic, he believes, yields a moderate middle ground—neither “too assertive nor too timid”—that places as many demands on citizens as it does on immigrants. Immigrants must make an effort to learn English and become acquainted with civic principles and American culture; and for their part, citizens must facilitate and encourage the assimilation of immigrants into the community through a combination of government programs and voluntary citizen-group activities.

Pickus sees “perennial tensions” between “civic ideals” and “national belonging.” His prescription for overcoming these tensions is to advocate what he calls a “contemporary civic nationalism” that “emphasizes the need to account for actual practice in spurring attachment and engagement, rather than relying only on core values, universal rights, cultural cohesion, or racial identity.” This “supple and versatile” nationalism “seeks to bridge the gap between immigrants’ needs and interests…and the values, rituals and practices of American life.” It recognizes the claims to legitimacy advanced both by “principles and peoplehood.” Pickus argues, in short, that civic principles alone—those political principles derived from the Declaration of Independence and embodied in the Constitution—are not sufficient to inspire the sense of belonging that is essential to “peoplehood.” Such community requires “an emotional or organic bond” that abstract ideals and principles cannot satisfy.

Nationalism is still necessary for Pickus, and “as a practical matter, the nation-state remains the primary vehicle for protecting rights and practicing democracy.” But American immigration policy should not be driven by the kind of “illiberal nationalism” that pursues “discriminatory and divisive” measures like California’s Proposition 187. Nor should America adopt polices that are “contradictory, such as increased border enforcement coupled with provisions for new amnesties for illegal aliens,” or simply hypocritical, such as attempts to limit health care for illegal aliens given “the economy’s heavy dependence” on cheap, unskilled labor.

Pickus is correct about the core problem now facing America, a problem that was not caused by America’s immigration policies but certainly has been exacerbated by them. “Today,” he argues, “Americans face the difficult task of sustaining a civic nation in the absence of a dominant culture, ethnic identity, or consensus on the meaning of constitutional values.” In fact, according to Pickus, “Americans have never agreed on the meaning of their core principles.” What, then, can we ask immigrants to assimilate to? If we cannot agree among ourselves, what kinds of demands can we make upon them? The lack of agreement suggests to Pickus that a “holistic model of citizenship” is the most realistic way forward. This newfangled citizenship, drawing on both sides of the current debate, upholds “broader cosmopolitan commitments” that would help “engage citizens in negotiating multiple identities and institutional relations,” but at the same time it emphasizes “a sense of attachment to a broader whole that integrates those commitments.”

In fact, Pickus claims that this was the vision of some of the founders, most notably James Madison and John Marshall, as well as of some of Progressivism’s leading lights, like Theodore Roosevelt and social critic Randolph Bourne. Pickus’s proof that Madison and Marshall adhered to this brand of civic nationalism is, however, tenuous. Leave aside, for the moment, their particular views on the Alien and Sedition Acts, which the book discusses at length. The larger point is that neither Madison, nor Marshall, nor any other American founder perceived the conflict between civic principles and the requirements of community that Pickus does.

The Progressives, on the other hand, did see such a conflict. They saw the static, outmoded principles of the founding as an unnecessary brake on the Darwinian evolution of human dignity. Under the Progressives, the Constitution became a “living document,” its principles constantly in need of revision. Although Pickus wants to split the difference between the founding principles and Progressivism, he eventually sides with the latter, writing that “there is no single balance between principles and peoplehood that is good for all time. Instead, policies and institutions must be modified and adapted to meet contemporary challenges.”

It is true that there were debates among the founding generation about policies regarding citizenship and immigration and that these debates were complicated by the presence of slavery. But there was also enough principled agreement among the founders that Thomas Jefferson could speak of the Declaration of Independence as an expression of the “American mind.” If we believe that those principles are no longer applicable to our present circumstances—as Pickus sometimes seems to suggest—then maybe we should discard them. But if we believe that those principles are still viable, don’t we have an obligation to restore them to the extent possible?

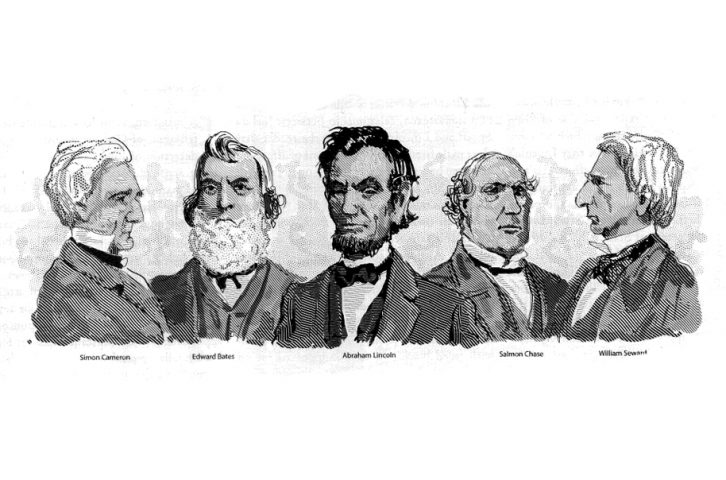

For Abraham Lincoln, it was a shared sense of constitutional principles that ultimately provided the genuine basis for American citizenship. These principles formed an “electric cord” that united Americans and incorporated immigrants into “blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration.” The principles themselves did not have to change to stimulate emotional or patriotic attachment to them, much less to accommodate “multiple identities.” In Lincoln’s view, multiple identities became one identity—an American identity—by reverent allegiance to the principles that animate our common political life. Perhaps the recovery of the founding principles will prove difficult—even impossible. But talk of cosmopolitan citizenship as if it were the only alternative where there is no “consensus on constitutional values” jeopardizes what is best about American citizenship.

Pickus argues that the framers relied on contradictory principles as the ground of citizenship: they tried to combine consent with the common-law notion of birthright citizenship. But here this otherwise careful and dispassionate scholar is mistaken. The Declaration clearly makes consent the ground of citizenship and this was explicitly incorporated into the 14th Amendment. Birthright citizenship, as Blackstone explains, is a feudal doctrine, the ground of subjectship, not citizenship; it requires perpetual allegiance. This feudal legacy was repealed by the Declaration of Independence as Americans threw off their perpetual allegiance to the crown.

Furthermore, our tolerance of dual citizenship debases and degrades the idea of citizenship altogether. Jacob Howard, the author of the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause, implied that American citizenship required “exclusive allegiance.” A pledge of exclusive allegiance is still required in the oath of citizenship, although the State Department now permits dual citizenship. Eighty-five percent of all immigrants arriving in America come from countries that allow—indeed encourage—dual citizenship. We have the absurd situation in which a newly naturalized citizen can swear exclusive allegiance to the United States but retain his allegiance to a vicious despotism or a theocratic tyranny.

* * *

Pickus sees dangers in allowing multiple citizenship—”fragmentation and alienation”—but he alleges that there are benefits, too. A prudent approach to multiple citizenship, he claims, “supports individuals’ commitments to multiple polities and peoples, thus enlarging communal identity in the wake of economic and political globalization.” Multiple citizenship also facilitates “the spread of transnational communities of descent, diasporic communities whose members have sought to strengthen democratic arrangements in their home countries.” In his view we must face the fact that multiple citizenship seems to be the wave of the future and prudent accommodations are necessary. But in that case, of course, it would no longer be possible to speak of exclusive allegiance, let alone the “true faith and allegiance” of his book’s title.

Although Pickus clearly recognizes these difficulties, his prescriptions are driven by the constant attempt to seek a middle ground where none exists. In a system of multiple allegiances, no one would have any allegiance properly so called. His effort, ingenious and undoubtedly well-intentioned, to combine the American Founders and the Progressives is similarly unpersuasive. Swearing “true faith and allegiance” to a regime that is continually under construction and informed by progressively evolving principles would be strangely hollow, to say the least.