Books Reviewed

A review of Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet , by Jennifer Homans

, by Jennifer Homans

Throughout history ballet has been intricately linked to politics and political change: it is rooted in the 17th-century French court, where it shaped etiquette and rank. Such aristocratic frivolity fell out of fashion during the French Revolution but was embraced in Imperial Russia, where ballet blossomed with Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake. By the Soviet era, ballet had become a Russian tradition and a useful and popular non-verbal art form. In Britain during World War II, ballet was also a rallying point, with Margot Fonteyn becoming an onstage heroine. As the Cold War played out, America, the adopted home of the 20th century's genius choreographer George Balanchine, enjoyed a ballet renaissance.

This story unfolds with smooth narrative pacing in Jennifer Homans's Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet. Readers with a deep knowledge of history, especially political history, will find it an engaging read that looks at familiar events from an artistic perspective. And happily, one need not have prior knowledge of ballet to draw from the book a rich understanding. Homans, the dance critic for the New Republic and a former dancer herself, turns out to be an excellent historian.

But Homan's well-mannered history becomes a eulogy by the end. Ballet, she argues, is a fading art, stalled in a time loop of the 19th-century classics with only an occasional performance worth watching. "After years of trying to convince myself otherwise," she writes,

I now feel sure that ballet is dying. The occasional glimmer of a good performance or a fine dancer is not a ray of future hope but the last glow of a dying ember, and our intense preoccupation with re-creating history is more than a momentary diversion: we are watching ballet go, documenting its past and its passing before it fades altogether.

But this is a difficult argument to make. Once the reader reaches Homan's sad epilogue, he has already turned 539 pages describing a pattern of highs and lows across cultures, regimes, and countries. Why should this particular low—if you believe that 21st-century ballet is at a low—be the last one?

Homans sets up a persuasive case based both on the particulars of the industry (which I won't address here) and the facts of contemporary culture, worth exploring even for those of us who do our best dancing at weddings. Perhaps her strongest point is her first:

Ballet has always been an art of belief. It does not fare well in cynical times. It is an art of high ideals and self-control in which proportion and grace stand for an inner truth and an elevated state of being.

Ballet is earnest. it is not haphazard, detached, louche, or ironic. It is a search for perfection that transports viewers away from the consciousness of their own aching bodies and troubled lives. In specific times and places, it has offered an escape-from harsh realities like Soviet violence, or wartime impoverishment. But when compared to, say, the guitar riffs of a post-rock indie band wearing t-shirts and sneakers, ballet's idealism looks uncool.

* * *

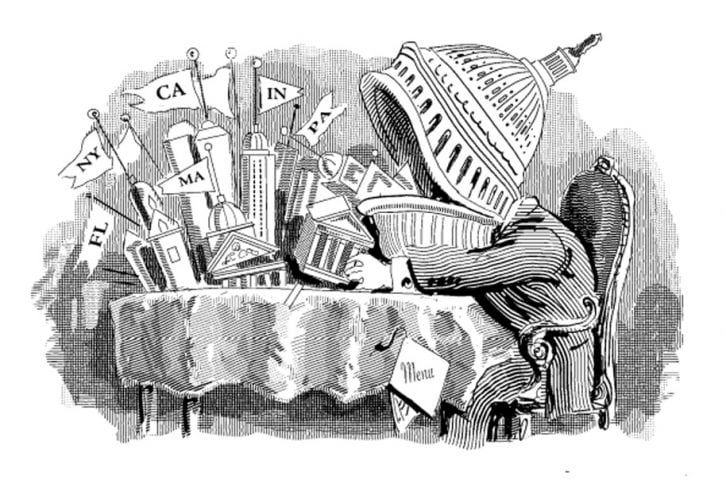

Homans further argues that in our culture, striving is viewed with suspicion: "We are skeptical of elitism and skill, which seem to us exclusionary and divisive." Yet mediocrity in ballet is a wretched sight. The training system is emphatically opposed to the "every kid is a winner" attitude. Legions of little girls and boys go to ballet classes every Saturday in this country, and in every class, the best are asked to stand in front so they can lead the others. The gifted children are apparent by the age of 10 or 11. If they have talent, they may advance, but entry into the elite companies goes only to a handful: New York City Ballet has 24 principal dancers; American Ballet Theatre has 17. Students' chances are as slim as their waistlines.

Homans observes correctly that the industry has largely ignored its audience. "As for the people," she writes,

they have been forgotten. Not only in boardrooms preoccupied with the next gala, but by scholars, critics, and writers. Dance today has sunk into a recondite world of hyperspecialists and balletomanes, insiders who talk to each other (often in impenetrable theory-laden prose) and ignore the public. The result is a regrettable disconnect: most people today do not feel they "know enough" to judge a dance.

For three years during my late 20s, I wrote the dance criticism for the New York Sun. I attended performances regularly, and I often brought along guests who had never been to the ballet. Many found it totally foreign. It was a pleasure to introduce them to the art form. But it was also painful to think that ballet's message of beauty and idealism was simply not reaching them.

* * *

This may not be ballet's fault. we are living, as Homans goes on to explain, in "fractured, niche environments and virtual ‘communities' based on narrow personal affinities rather than broad common values." This is a general complaint about technology that is not exclusive to ballet. The leaders of many fields, especially in the arts and humanities, would likely agree with it. Why are people posting pictures of their pets on Facebook instead of reading literature? Why are they tweeting with total strangers instead of going to the theater with their friends?

Of course, technology may not have a purely negative effect on the arts. In the past, ballet has flourished or withered due to political revolution. What will the long-term effects of the digital revolution be? Homans writes, "If we are lucky, I am wrong and classical ballet is not dying but falling instead into a deep sleep, to be reawakened—like the Sleeping Beauty—by a new generation." The internet hastens and expands the dissemination of information, which could serve ballet well. Audience members who are curious about a dancer, a choreographer, or an upcoming show can often watch a preview by poking around YouTube. In early 2011 TenduTV, a New York-based distributor of dance films, persuaded Apple to include ballet titles on iTunes. One of the most informative series about dance, the Guggenheim Museum's Works & Process, has begun streaming live over the web and tripled its audience in its first broadcast. The dance community is among the most active on Twitter. And ballet has followed opera's lead: performances are being broadcast in High Definition to cinemas. Any art form can use these same tools to make its voice heard.

But unless ballet offers the culture something newly vital, the social media, marketing, and videos will be nothing but noise. It's possible that the necessary vitality will arise as an indirect effect of technology: as communication continues to move at a frenzied pace and as we absorb information in ever smaller bites, human beings will eventually need to seek out mental refuge or imaginative space.

One might say this is what happens in every act of reading. But we are now so attuned to instantaneous communication that if the little light on the BlackBerry blinks or the phone rings anywhere in one's vicinity, the imaginative event taking place in the brain is disrupted. Theaters are among the few places where one is safe from these interruptions; cell phones and other electronic devices are forbidden-by law, in some places. Ballet, in particular, offers a unique counterbalance to the cacophonic world our short attention spans have created.

In 1956, the cognitive psychologist George Miller published a paper that became a classic: "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information." His point was that the brain can concentrate on seven objects or concepts-plus or minus two-at a time. Other research suggests the number may be lower. Abstract ballets, for example those created by Balanchine with music by Stravinksy, often combine music and dance so smoothly that the brain can perceive them as one. In the case of story ballets, there is an entire narrative arc to follow without the interruption of words. At its best, ballet is unified; it eliminates the need to engage with dialogue or lyrics, which sets it apart from theater and opera. This is not to suggest that ballet is an art we watch by kicking back and going numb-as we often do with television and movies. What's unique about ballet is the level of attention required-movement engages the eye, music engages the ear, and if all goes well, we are swept away by our imaginations.

What's more, the physical skill required for ballet can hardly be denied. Watching people of exceptional ability in a live performance punctures the low expectations set by so many television shows and movies. Opera is experimenting with 3-D projections to create ever more fantastic visuals, but ballet doesn't need projections to make it absorbing. It inspires with the human body alone.

* * *

This, admittedly, is a hopeful view. For ballet to undergo a renewal, ballet companies must tap into the sensory benefits of the art, and aggressively counteract the social or cultural reasons that cause people to shy away from it. That's a tall order. But Homans suspects that

if artists do find a way to reawaken this sleeping art, history suggests that the kiss may not come from one of ballet's own princes but from an unexpected guest from the outside-from popular culture or from theater, music, or art; from artists or places foreign to the tradition who find new reasons to believe in ballet.

What we learn from Apollo's Angels is that the development of ballet has been sparked again and again by external, often political, events. If we're lucky, maybe ballet can find its next catalyst in something short of revolution.