When I ran for re-election to the United States Senate from New York in 1976, it was my misfortune to have Daniel Patrick Moynihan for an opponent. (He won handily.) During our first encounter, Pat told the audience that although I was a fine fellow, I was stuck in the 18th century. I confessed that I was guilty as charged and acknowledged my total commitment to the principles embedded in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The crucial question, of course, is whether those 18th-century principles remain relevant to the vastly changed world we live in now. They were realists who understood that the human drive to accumulate power had been the historic enemy of freedom. They therefore incorporated two safeguards into the Constitution—its system of checks and balances, and the principle of federalism. Describing the latter in The Federalist, James Madison explained:

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government, are few and defined…. [T]he powers reserved to the several States will extend to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State.

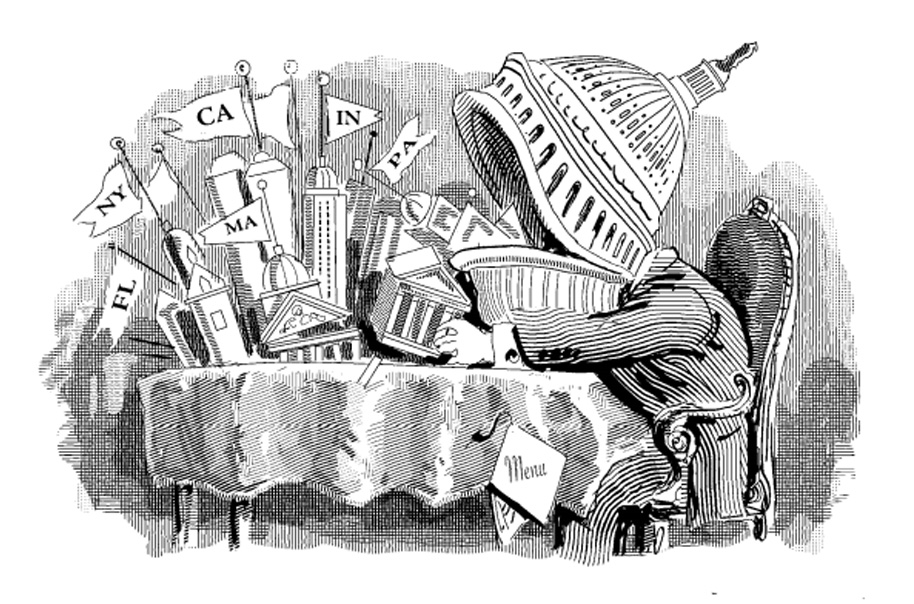

This division of labor accords with the venerable principle of subsidiarity, which allocates governmental responsibilities to the lowest levels able to exercise them. The effect is to ensure that governmental decisions most immediately affecting people's lives will be made by officials who are the closest to them and have the most intimate knowledge of the relevant facts and conditions. This design served us so well during the first 150 years of our national existence that the eminent British historian Lord Acton, declared that our constitutional development of federalism "has produced a community more powerful, more prosperous, more intelligent, and more free than any other which the world has seen." Over the years, however, our federal government has engaged in massive raids on the constitutional prerogatives of the states. Today there is virtually no governmental responsibility beyond the reach of federal authority. As a consequence, our nation has been converted into an administrative state overseen by unelected officials who issue regulations that reach into every corner of American life. Few appreciate the extent of this transformation. In 1935, at the outset of the New Deal, the United States Code consisted of a single volume containing 2,275 pages of statutes. Today, it comprises 30 volumes of statutory law. When I was in law school, Title 42, which contains the federal laws relating to public health and welfare, consisted of just 128 pages. Today it contains over 6,200 pages, more than twice as many as the entire body of federal law at the beginning of the New Deal.

Bureaus and agencies issue endless marching orders to administer those federal statutes. By 2010, the Code of Federal Regulations contained over 166,000 pages of detailed, fine-print regulations that have the force of law and affect virtually every aspect of American life.

Of particular concern are federal intrusions on the responsibilities of the states through proliferating grant-in-aid programs. As a consequence of these initiatives, federal regulations guide transportation, housing, education, social services—everything, in other words, that Madison had anticipated the state governments would manage. Washington has been able to impose a drinking age of 21 and a 55-mile per hour speed limit by conditioning highway construction grants on a state's enactment of those limitations. Over the years, we have seen the states reduced to administrating federal policies rather than enacting their own.

Capacity to Govern

The question is whether the federal government's conversion into an all-encompassing administrative state will lead to a better life for most Americans. Consider, first, whether the federal government is competent to handle responsibilities beyond the core assigned by the Constitution. Washington, D.C., is immune to the disciplines of a competitive marketplace that promotes efficiency and weeds out failures. Once a federal law and its attendant regulations are in place, they are very difficult to change. This is so because of the laborious processes that bring them into being and because even the worst of them are apt to be protected by an "iron triangle," consisting of the legislators who brought them into being, the bureaucrats who oversee them, and those who benefit from the status quo, however flawed.

Misguided political decisions are to be found in state governments, of course, but one of the virtues of federalism is that the states are able to test a variety of approaches to common problems. Successes can be emulated and failures avoided. Furthermore, while Washington must issue one-size-fits-all regulations to states as diverse as Massachusetts and Utah, state governments are able to tailor their directives to their own specific conditions.

The second reason for reducing the scope of Washington's concerns is financial. The states have limited borrowing powers, and so they are ultimately restrained by the willingness of their citizens to be taxed. The federal government, however, has a virtually limitless ability to borrow. It follows, therefore, that reducing the scope of federal responsibilities to those that are beyond the competence of the states will reduce the occasions for fiscal irresponsibility.

Finally, there is the cost to Congress and the quality of government itself. Once upon a time, the Senate was referred to, with reason, as the world's greatest deliberative body. But that was long, long ago, when Congress was in session no more than six or seven months a year and its members had the time to study the bills under consideration and hear the merits debated. They could do so because Congress limited itself to the half-dozen areas of responsibility assigned to it by the Constitution.

Who Does What?

Congress today is a radically different institution. In early 1971, when I first arrived in Washington, a contemporaneous study of the inner workings of Congress concluded that the workload of the average congressional office had doubled every five years since 1935. I can certify that during my own six years in office, I witnessed both a sharp increase in the Senate's already frenetic pace as well as an equally sharp decline in its ability to get very much done that could honestly be labeled thoughtful. The House suffered the same decline.

This is no reflection on the quality of current members of Congress. The simple fact is that their days are so fractured by competing claims on finite time that they have too often found themselves incapable of handling even their most fundamental obligations. Last year, Congress failed to adopt a single appropriations bill, thereby requiring the current Congress to wrestle with the continuing spending resolutions needed to enable the federal government to pay its bills. Admittedly, Congress did manage to enact a monumental piece of healthcare legislation. But whether one agrees with its specific objectives or not, the manner in which it was written and passed illustrates everything that has gone wrong with Congress in recent years. There was no thoughtful examination or debate of the myriad provisions within its 2,700 pages, because they weren't available in final form until hours before its members were pressured into voting it into law.

Congress's erratic performance is in large degree the result of a workload that has grown too great to permit either reflection or attention to detail. It reflects the fact that at the national level we are rapidly losing our capacity for government in which politically difficult decisions can still be made, problems thought through to ultimate solutions, and long-term commitments undertaken in the confidence that they will be honored.

There are no doubt many causes for the increasing quantity and diminishing quality of federal regulations and laws, but the most significant of these has been the virtual abandonment of the principle of federalism. Accordingly, I believe the surest road to true reform is to reduce the scope of federal responsibilities to manageable, constitutional size.

It is neither possible nor even desirable to replicate the division between state and federal authority that once obtained in this country, and that until relatively recently was thought to be constitutionally mandated. Too many fundamental changes have occurred in American life. What I do urge is the reaffirmation of the original constitutional design in which only those functions that are deemed essential to the effective conduct of truly national business are assigned to the federal government, while all others are reserved as the exclusive province of the states. We should then determine, in the light of today's conditions, which level of government should be doing what.

A return to federalism, however, will be anything but easy. If those who gravitate to Washington don't like the way the citizens of Illinois, or Hawaii, or Arkansas choose to manage their own affairs, they will have to suppress the impulse to impose enlightenment on them. In the fullness of time, Washington could learn to set aside the assumption that the citizens of the several states cannot be trusted to govern themselves. Perhaps it is not altogether romantic to hope that necessity, if not philosophy, will lead us to rediscover the robust federalism that in times past has provided this nation with such extraordinary strength, opportunity, and freedom.

* * *

For Correspondence on this essay, click here.