Books Reviewed

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars—on stars where no human

race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

—Robert Frost

Picture Cormac McCarthy in Ibiza. Before anything else, picture the flush young author in the late ’60s, as he was never then or afterward seen in the public eye: tooling around that wild island off the coast of Spain in a yellow Jaguar convertible, accompanied by his second wife, Annie, and often by another up-and-coming writer, Leslie Garrett—he and Cormac both recent award winners, living high and savoring success. Picturing McCarthy this way suggests a worldly side to the Knoxville-raised novelist, who made his reputation initially by putting his Southern Gothic impress on landscapes far closer to home, writing novels wherein the narrator names for you all the hardwoods in darkest Appalachia, while splitting open on his pitiless chopping block the hacked and scored wood of which man’s own dark heart is made.

After 1979, he turned his attention to the Texas and Mexico borderlands, which got him parodied in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) as a sham philosopher-poet of the West, a romancer of the sagebrush. But McCarthy was no Larry McMurtry; romantic nostalgia was never his métier. Few novelists of his rank have produced work so fixed in the bedrock of the American story. With his passing in June 2023, just months after his final works of fiction appeared in print, we have the chance to see his variegated achievement whole.

A sense of fatedness attends his career. Upon blind submission of his first novel, The Orchard Keeper (1965), he landed a deal with William Faulkner’s own editor at Random House, Albert Erskine—Faulkner called him “the best book editor alive today.” That same novel, about bootleggers in rural Tennessee, went on to win the William Faulkner Foundation Award. “Sometimes things get handed to you,” McCarthy later wrote, in another context, “just because you’re the only one there who won’t drop them.” It is impossible to do justice to the author of Suttree (1979) and Blood Meridian (1985) without indulging in this sort of mythmaking (the literary equivalent of a fresh-faced Bill Clinton shaking President John F. Kennedy’s hand). That is why episodes like the bohemian spell in Ibiza serve as useful counterpoints. If one can’t help printing the legend—if the contours of that legend do in fact correspond at many points to the actual life—one can at least propose alongside it a counterlegend, a counterlife. McCarthy’s biography, like his legacy, is more many sided than is often supposed.

Swept Along by Circumstance

Born in 1933 in Providence, Rhode Island, but raised in Knoxville from the time he was four years old, McCarthy briefly attended the University of Tennessee before serving four years in the Air Force. Stationed in Alaska for two years, he began to read avidly for the first time in his life. After being discharged he returned to the university and published two stories in the campus literary magazine—the only short stories he ever published—under the byline of C.J. McCarthy, Jr. (Born Charles Joseph, he later changed his name to Cormac, after the Irish king.) Though he eventually dropped out for good, his first literary honors date from this time: he won the Ingram Merrill Award for creative writing two years running, in 1959 and 1960. Before his first novel was even out—he wrote it while working at an auto parts warehouse in Chicago—he scored a traveling fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

This set the pattern for the next two decades: grants and fellowships (from the Rockefeller, Guggenheim, and MacArthur foundations) kept soul and body together while he wrote with Erskine’s fatherly indulgence a series of novels, each darker and more difficult than the last. First, Outer Dark (1968), a bleak picaresque about a mother’s doomed efforts to locate her abducted child, the product of incest with her brother. Then Child of God (1973), a fiction based on the real-life travails of a serial killer in Sevier County, Tennessee. Suttree, the culminating masterpiece of his Appalachian phase (built around the antics of a sensitive, houseboat-dwelling spalpeen and his rogues’ gallery of associates) is the only entry in this early sequence whose violence and squalor are leavened by plenty of humor.

None of the books sold in hardcover more than 5,000 copies, yet McCarthy’s stubbornness and self-belief were such that he refused to supplement his income by teaching, lecturing, or writing magazine pieces. This despite living with his first wife in an unheated shack that lacked running water in the foothills of the Smokies, then with his second wife “in total poverty”—her words—in a dairy barn he renovated near Louisville, Tennessee. Both marriages ended in divorce. Yet meanwhile, the ranks of his literary admirers grew to include Ralph Ellison, Robert Penn Warren, Anatole Broyard, and Guy Davenport. More enthralling than his storytelling was McCarthy’s distinctive prose: rich, molten, direful, and largely unpunctuated, carrying the reader along like a lava flow. It is a style that apprehends with almost painful clarity the things of this world while drawing out of them their full suggestive import, bringing to bear on even the simplest operations tremendous metaphysical pressure. Here is John Grady Cole from the later novel All The Pretty Horses (1992), 16 years old and in love:

The fire had burned to coals and he lay looking up at the stars in their places and the hot belt of matter that ran the chord of the dark vault overhead and he put his hands on the ground at either side of him and pressed them against the earth and in that coldly burning canopy of black he slowly turned dead center to the world, all of it taut and trembling and moving enormous and alive under his hands.

McCarthy sounded like Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor until he came to sound like himself, maintaining at the level of sentence and paragraph a sustained excellence that is hard to believe (Saul Bellow referred to “his life-giving and death-dealing sentences”). His chosen demesne was what he proclaimed it to be in the title of his second novel, Outer Dark: an achingly real American—and, later, Mexican—landscape that is also a kind of cosmic void. The scholar Bernard T. Joy once told me that he sees the ignorance of McCarthy’s characters concerning their roots “as setting up a kind of blind determinism that sweeps [them] along against their will almost, leaving no opportunity for real reflection or change.”

Meanwhile, McCarthy himself was being swept along by circumstance: broomed from a $40-a-night room in the French Quarter of New Orleans, he later shacked up in a friend’s Knoxville motel. There he got word in 1981 that he had won the MacArthur Foundation’s so-called “genius” grant, worth nearly a quarter of a million dollars. This proved life changing in two ways. First, it put him in touch with Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann, who had discovered the quark (and named the exotic particle after a word he happened on in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake). Gell-Mann would give McCarthy the only lasting institutional position of his life, making him the writer in residence—and later a board trustee—of the gigabrained Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a position he held until his death. More crucially still, the grant made possible the research and extensive travels that informed his magnum opus: Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West.

War Is God

It is the center and circumference of McCarthy’s oeuvre, black hole and white-hot accretion disc in one, so that everything before and after seems to be falling toward or issuing from it, this one book, Blood Meridian. A singularity. Unfilmable in a way that McCarthy’s other crucial Westerns are not, unsurpassable as a novel because it is less a novel than a prose epic, an American Iliad—oceanic in the blood-dimmed tide of its action.

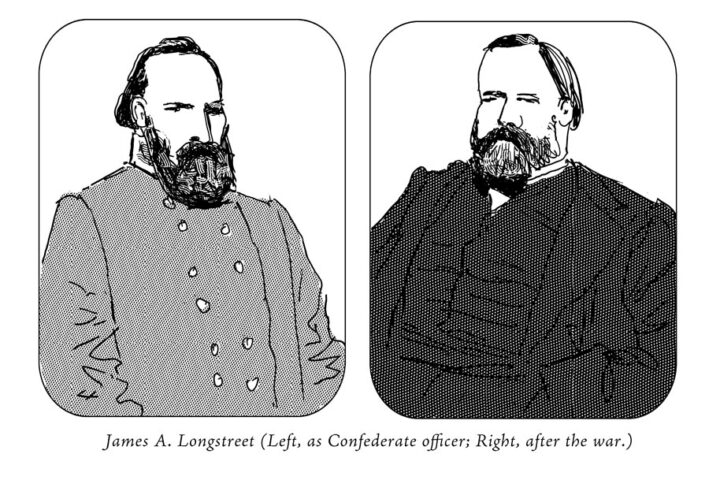

The plot is simple enough: a teenage boy runs away from home and falls in with a band of mercenaries who are contracted by the governor of Chihuahua, Mexico, to deliver Indian scalps. Their atrocities soon redound on their heads; the action seesaws back and forth as the marauders alternately hunt and are hunted across a wilderness remote and alien as the moon. There is a dreadful exuberance to the action. The saturnalia of slaughter is rendered in highly aestheticized prose that affords the reader some distance even as it depicts the carnage with staggering force. The very land about the mercenaries is redolent of violence primeval: “Sparse on the mesa the dry weeds lashed in the wind like the earth’s long echo of lance and spear in old encounters forever unrecorded.” The gang’s misadventures are based on real events that happened in 1849 and 1850; McCarthy said he would “rather dig ditches” than do all that research again. But Blood Meridian transcends its sources as it uncannily transcends its apparent genre.

Among the hired killers, urging the mayhem on like a concealed god of archaic myth, there travels a huge, terrifying, and apparently ageless albino known as Judge Holden. He is a faultless (and ambidextrous) shootist, a masterly rider, first-rate fiddler, well-traveled polyglot, talented sketch artist, skilled natural historian, and enthusiastic assassin utterly devoid of pity or scruple. The air around the judge practically hums with visionary psychosis. Like a preternatural archon of war, he expounds his theology of violence in a series of speeches so remorseless in their eloquence and so unsettling in their implications that perhaps only Captain Ahab and Macbeth in our literature reach equivalent heights. His doctrine of bloodletting derives chiefly from the following two fragments of Heraclitus:

War is the father of us all and our king. War discloses who is godlike and who is but a man, who is a slave and who is freeman.

It must be seen clearly that war is the natural state of man. Justice is contention. Through contention all things come to be.

The first of these McCarthy set down in his notes for the novel. On the judge’s lips, it becomes:

The selection of one man over another is a preference absolute and irrevocable…. This is the nature of war, whose stake is at once the game and the authority and the justification. Seen so, war is the truest form of divination. It is the testing of one’s will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select. War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god.

“All power is of one kind,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson in a late essay, “a sharing of the nature of the world.” The judge swerves from this fundamental insight, insisting that power consists rather in forcing the world, through mortal combat, to take sides—to choose between incompatible futures. If the Iliad is a “poem of force,” as Simone Weil claimed, Blood Meridian is its companion in prose. On first reading it gave famed critic Harold Bloom nightmares. By the turn of the millennium—having since read the novel scores of times—he was lauding it as the greatest literary work by a living American.

While the likes of Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo (and, later, David Foster Wallace and William T. Vollmann) were rendering America as a postmodern cartoon, McCarthy was heading backward and downward in time, seeking the origins of things. These were to be found in atavistic violence, certainly—a newspaper report concerning a 300,000-year-old skull that appears to have been scalped serves as an epigraph to Blood Meridian. But he drew also on physics and advanced mathematics, about which he talked incessantly at SFI and which informed his final pair of novels. Math, he opined, is “like music: you can’t really say what it is, or why does it do what it does.”

Unflinching intellectual inquiry is everywhere in McCarthy. There are academic papers to be written on the radical Wittgensteinian skepticism that runs through his work. A man questions the nature of evil, only to discover that he lacks a “working definition of evil” by which to proceed. In the end, he decides that “the one thing that characterized all evil everywhere was the refusal to acknowledge it. The eagerness to call it something else.” In a tragic final encounter between the kid and the judge, years after they rode together, the kid says defiantly, “You aint nothin.” To which the judge replies: “You speak truer than you know.”

A Chain of Books

By the time Oprah Winfrey chose McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic quest novel The Road (2006) for her book club in 2007, the gothic tropes of appalling Appalachia had given way in his fiction, first to widescreen narratives of men and beasts in the Border Trilogy—inaugurated by All the Pretty Horses (“the dogs were lean and silver in color and they flowed among the legs of the horses silent and fluid as running mercury”) and completed with The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998)—and then to bleak, austere novels of the end times (No Country for Old Men [2005], The Road). Having benefited early on from an editor who stuck by him through book after uncommercial book, McCarthy—who for decades had no agent—later benefited, at Random House, from the marketing power of a huge publishing conglomerate. His new professional handlers helped establish the book-to-screen pipeline which in 2000 turned All the Pretty Horses, his breakthrough novel, into a Hollywood spectacle starring Matt Damon and Penélope Cruz.

In the mid-’90s, McCarthy also began to publish plays for stage and screen. Vanderbilt University professor Vereen M. Bell’s perceptive book, The Achievement of Cormac McCarthy (1988), explains how in his work “experience is a sustained dialectical striving,” for which resolution is impossible. McCarthy’s dramatic works are engines of dialectic. The philosophical investigations and discursive commentary that in his novels take a back seat to lyrical descriptions of landscape and to the stoic urgency of human striving here come to the fore. Characters quote Montaigne, debate the existence of God, ponder the mysteries of cetology. They recite touchingly the poetry of Dylan Thomas and Ezra Pound. An avowed materialist, McCarthy nevertheless couldn’t stop wrestling with questions of religious faith and the nature of being. The Stonemason (1994) is full of Biblical motifs, and The Sunset Limited (2006) pits a good Samaritan ex-con, Black, in an escalating argument against an atheist professor, White, whom he has saved from jumping in front of a train. The stakes are nothing less than White’s life, and perhaps his soul.

McCarthy’s final work of fiction, Stella Maris (2022), reads like a play for two voices. Composed entirely of dialogue, it is the story of Alicia, a young mathematician with a genius-level IQ, in love with her brother, who currently lies in a coma but will rise again, after her death, as the protagonist of The Passenger (2022). Alicia alternately argues with, mocks, shocks, frightens, confuses, and finally confesses all to a psychiatrist who wants to turn her into a case study. David Krakauer, president of SFI, said McCarthy was drawn to individuals with a “superintelligent disregard for the status quo,” a lordly indifference the author shared. (He edited several of his SFI colleagues’ books.) Yet his brilliant characters are cautionary tales about the limits of reason. “If you look at the history of species,” marine biologist Guy Schuler says in McCarthy’s unpublished screenplay Whales and Men, “there seems to be no selective advantage to intelligence.” For reasons as much intellectual as emotional, Alicia, like White, is driven to suicide.

Books are made out of other books, McCarthy once said. He never warmed to Marcel Proust or Henry James. His body of work belongs not to the tradition of the social novel, of which James and Jane Austen and Charles Dickens are the chief luminaries in English, nor to the fiction of introspection. His chief debts are to the Herman Melville of Moby-Dick, to Joyce and Faulkner and O’Connor, to Shakespeare and Ernest Hemingway. If it did not foregound “issues of life and death,” the fictional enterprise for McCarthy had no valence. Perhaps inevitably, Hemingway’s spirit hovers over the Border Trilogy. Men contending with beasts, the elements, and other men; men crazed with vision, possessed of monomania that admits no competing claims; men on the margins, exiled or self-exiled—such are the protagonists and subjects of the fevered tradition McCarthy joined and extended. Such indeed are the pioneers, Puritans, revivalists, military prodigies, and “strong transgressor[s], like Jefferson, or Jackson” (Emerson’s memorable phrase), who formed and informed the American imagination, part of a national mythos embracing Valley Forge, Shiloh, and the Western frontier.

In America today the legacy of this tradition is largely cinematic: Westerns, gangster movies, war epics. Drunk on landscapes—“beautiful, inconsolable landscapes,” the poet Robert Hass called McCarthy’s fictional territories—which serve as the arenas for violent action, McCarthy’s doomed outcasts work out their destinies without the aid of family or community or church, unbound by law or custom. “Here beyond men’s judgements all covenants were brittle,” the author tells us. His men smoke in silence; they spit into campfires by way of passing comment. They extricate themselves from danger by acts of will or not at all.

Wrack and Ruin

What ultimately links together the characters in all McCarthy’s various periods is neither masculine stoicism nor alienation, but deprivation. Weil had in mind this harsh reality when she wrote, in her Iliad essay, “Nearly all of human life, then and now, takes place far from hot baths.” Whether it is John Grady Cole and his cousin eagerly lighting out for the territories in All the Pretty Horses, or pitiable, depraved Lester Ballard hiding out in a cave in Child of God, hot baths are hard to come by in McCarthy’s fictions. Home is a provisional and threatened thing. In one of the most moving parts of The Passenger, an old woman describes the astonishing methods by which her grandfather and uncle built their rural homestead, followed by the trauma of its ruination at the hands of the federally empowered Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA):

I dont know how they knew to do what they done, Bobby. I want to say that they could of done anything. They didnt even own a book. Other than the Bible of course. I dont reckon they hardly even had a sheet of paper. I always thought it was a good thing that God dont let us see the future. That house was the most beautiful house I ever saw. Ever floor in it was solid walnut and some of them boards was close to three foot wide. All of it hand planed. All of it at the bottom of a lake.

In the 1930s, the TVA—signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—sent agents door to door serving thousands of families with eviction notices to make way for a hydroelectric dam. In McCarthy’s telling, the flooding of the ancestral home is a senseless cataclysm. (Has anyone noticed that his father worked as a TVA lawyer for more than 30 years?) His political views are not on record, yet if he is a partisan of anything it is of the beautiful and local, the homegrown and handmade and irreplaceable. His critics are wrong to say that he ignores society and institutional life: rather, he takes sides against them. McCarthy’s characteristic mode, apart from gallows humor, is unsentimental elegy, a tightrope walk few novelists can perform—and fewer attempt, since many authors now put group identity foremost and openly profess beliefs which call for the application, against the local and individual, of state power.

The old ways die hard, he knew. Peter Gregory in Whales and Men is an Irish aristocrat whose family’s manor house is crumbling before his eyes. Everything is slowly going to wrack and ruin. Showing an American guest about the grounds, he says, “All of this was under cultivation when I was growing up. Periodically they would plow up old armaments and the bones of men and horses. We’ve a bloody history. Not done with, either.” The plural pronoun should be read as referring not to the Irish, but to mankind. For McCarthy, history is never done with us, even or especially if we can’t fathom our place in it. Sifting bones and compressing fossils, time makes strange what it doesn’t erase altogether.

Such themes had preoccupied him since at least his 1959 short story, “Wake for Susan,” his first published fiction. He knew better than to believe that all those lost people and forgotten folkways would ever come back. “All the time you spend tryin to get back what’s been took from you there’s more goin out the door,” says the wheelchair-bound old-timer Ellis in No Country for Old Men. “After a while you just try and get a tourniquet on it.” At McCarthy’s darkest, all of history becomes merely “a rehearsal for its own extinction.” But he never stopped giving narrative shape to the past, nor finding memorable ways to portray all the rich specificity of a world that he suspected concealed, behind endless variations, a wholeness, wonderful or horrible by turns. The old woman of The Passenger—in which McCarthy returns imaginatively to both Tennessee and Ibiza, embracing in his narrative sweep Hiroshima, the American Century, and the decline of the West—goes on:

You have to believe that there is good in the world. I’m goin to say that you have to believe that the work of your hands will bring it into your life. You may be wrong, but if you dont believe that then you will not have a life. You may call it one. But it wont be one.

Knoxville to El Paso to Santa Fe: McCarthy went his own way always, and despite imitators and a few heirs—the strongest of them was the late William Gay—he started no school, no movement. His name, unlike Kafka’s and Joyce’s, has not been adjectivized. When he was asked in interviews about himself, his books, or his writing process, there was a stark contrast between the Biblical sonorities of his prose and the stubbornly bland answers he proffered. Neither Oprah nor his physicist friends (Krakauer, Lawrence Krauss) could coax much out of him in public. He was determined to write himself into the tradition of taciturn American masculinity that figured so heavily in his work. Anyway, he told The New York Times, writing was “way, way down at the bottom of the list” of his interests.

The list was long, and ran the gamut of human endeavor. In The Passenger’s closing chapter we find Bobby, the protagonist, haunting Ibiza and Formentera as McCarthy once did—but not triumphantly, not at the wheel of a yellow convertible. He beds down in a disused grain mill; he builds fires on the beach at night alone. By lamplight he works problems left behind in the papers of the eminent mathematician Alexander Grothendieck. He finds an ancient bronze coin worn smooth by the centuries and ponders the peoples nourished in succession by the Mediterranean: Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines. “The inland sea. Cradle of the west. A frail candle tottering in the darkness”: he stands at the end of something. Studying the nostalgias, mourning equally his dead sister and the ages that are dead, he finds little to reassure him that civilization will endure. The surname his author gives him is Western.

We have yet to see McCarthy in full. The ostensibly stoic neo-cowboy loved great feasts, fine wines, and hours-long confabulations. He never tired of contemplating the efflorescence of culture in 5th-century Athens, and he considered Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater “the one iconic entity” in all 20th-century American art. He remained to the end of his life allergic to semicolons. For nearly 60 years he made indelibly his own the desert places of the heart, and of America.