Books Reviewed

Many conservatives claim the ability both to fight and think, but the skills often seem mutually exclusive. The activists’ books are tripe, and the thinkers’ activism is impotent—banal bestsellers and feckless white papers, respectively.

Christopher Rufo is the rare figure who speaks with authority and then translates that speech into political victory. He distills a notoriously abstruse field into a five-minute Fox News segment, which catches the attention of the president of the United States, whose chief of staff calls him the next morning to discuss an executive order, which abolishes the aforementioned ideology from the federal government three weeks later.

Two years ago, Rufo trolled leftist commentator Joy Reid into inviting him onto her MSNBC show. He proposed that they debate “critical race theory” (CRT), a once-obscure but influential academic movement that Rufo brought to the attention of the American public. Reid hardly let Rufo get a word in edgewise, but what he did say successfully stigmatized the term, spurring a rare leftist retreat in the culture war.

***

In his latest book, America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything, Rufo, now a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor of City Journal, spells out the arguments that justify and inform his campaign against CRT. “As an activist, I often have to communicate in small bursts of simplified rhetoric,” he explains in his preface. “As an author, I’m able to be expansive, tracing the patterns of history, exploring the intricacies of ideology, and plumbing the depths of the personalities that have shaped the way we think, feel, and act.”

Rufo tells a familiar story of how the Left conquered the universities and destroyed the country. We meet old friends such as the Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse and the terrorist Angela Davis—obligatory characters in any contemporary conservative polemic. But we also get acquainted with less familiar figures, in particular Paulo Freire, the Marxist whose Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) now haunts every teaching program in the country, and Derrick Bell, whose legal writing forms the basis of critical race theory.

These four horsemen of America’s apocalypse each herald a new stage of decay, dividing the book into four parts: revolution, race, education, and power. Even the familiar figures take on new life as Rufo’s meticulous research exposes new depths of radicalism. His tight narrative follows both intellectual and political history in a cycle that moves from the campus to the streets and back—rinse and repeat.

In Rufo’s telling, the New Left’s cultural revolution has reached its apotheosis, establishing a “substitute morality” throughout America’s elite institutions. Marcuse, more than any other thinker, set the revolution in motion. According to him, the United States had decayed into a “Welfare State and Warfare State,” incapable of realizing higher principles. Modern liberalism had robbed the people of their spirit, rendering them nothing more than “sublimated slaves” and “‘preconditioned receptacles’ for production advertisement, and domination.” Marcuse endeavored to remedy this sad state of affairs by seducing affluent whites, radicalizing impoverished blacks, capturing public institutions, and repressing his political opposition. The strategy worked.

***

Herbert Marcuse, for all his sins, possessed finely tuned faculties of reason and perception—as does Christopher Rufo, who describes the godfather of the New Left with a degree of detail and sobriety often missing in conservative polemics. It’s almost as if Rufo views Marcuse more as an example to be emulated than a kook to be mocked.

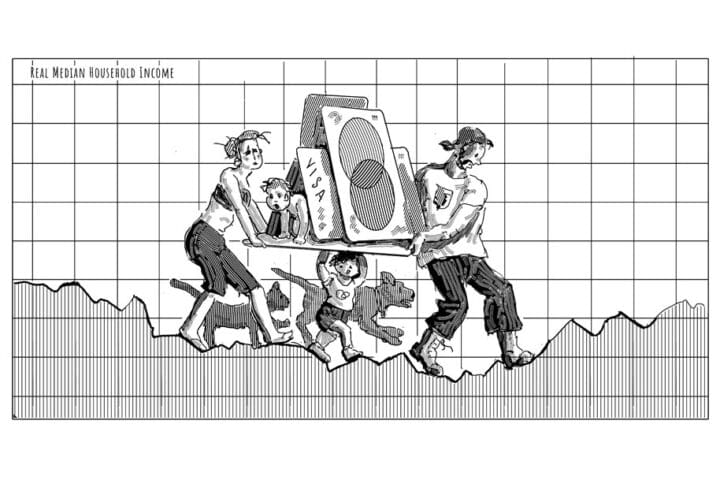

Marcuse observed that ghetto-dwellers of the 1960s existed “outside the democratic process.” The degraded state of their lives demonstrated “the most immediate and the most real need for ending intolerable conditions and institutions,” thereby rendering their opposition to the status quo “revolutionary even if their consciousness is not.” Today, that description better fits the “deplorable” underclass that elected Donald Trump than it does the coalition of supposedly marginalized groups that the Left has spent 60 years imbuing with institutional privilege and prestige. A clever conservative counterrevolutionary might capitalize on that fact.

Marcuse lamented how “the countercultures created by the New Left destroyed themselves when they forfeited their political impetus in favor of withdrawal into a kind of private liberation—drug culture, the turn to guru-cults, and other pseudo-religious sects.” Once again, that disastrous withdrawal from politics into private liberation better describes the Right today, which for at least a decade or two has largely forfeited the political order to the Left on the grounds that “politics is downstream of culture.”

Complacent right-wingers often imagine themselves in a mere battle of wits with left-wing radicals in the free marketplace of ideas. Rufo reminds us that the revolutionary Left wants to murder us. “The duty of every good revolutionary,” explained the militants of the Weathermen, the diehard remnant of the 1960s’ Students for a Democratic Society, is “to kill all newborn white babies” before they “grow up to be part of an oppressive racial establishment.” They added that this establishment already included some 25 million “die-hard capitalists,” all of whom had to die.

After their fit of youthful terrorism, the Weathermen retreated to the classroom. As Rufo shows in detail, half of the most active Weathermen found jobs in education. The leaders, who had laid bombs and killed people, found homes in prominent universities, where they helped to institute standards and norms that have rendered conservatives all but extinct on campus.

***

Enter Angela Davis, the lauded Communist intellectual and ringleader in the black liberation movement. Unlike her mentor Marcuse, Davis did not merely inspire acts of terror but planned and participated in them. Here again Rufo demonstrates his ability to translate dry scholarship into the evocative language of activism, pointing out that Davis called on her fellow travelers “to learn to rejoice when pigs’ blood is spilled.” She seduced prisoners to carry out her violent fantasies. She played the race card with sociopathic skill when she finally stood trial for her crimes. And she was acquitted.

Like the Weathermen, Davis and the black liberation movement ended up in the classroom, where Rufo observes a shift in tactics. On campus, he writes, Davis began “to strike at the origins of the nation’s historical memory, to expose its deepest principles as a pack of lies, and to break apart the cultural foundations that ensure its continuity.” In her telling, Abraham Lincoln didn’t free the slaves; at best, the slaves emancipated themselves. But really, slavery never ended. It only changed form and moved from the plantation to the prison, compelling Davis to demand the “abolition” of prison and, consequently, the system of laws—the regime—that it represented and enforced.

Rufo observes that this shrewd linguistic shift from “revolution” to “abolition” allowed Davis “to wrap her political program in the moral authority of the historical abolitionists while continuing to push for the same left-wing vision.” The Left failed when it attempted revolution through bullets and bombs; it succeeded when it employed the subtler tactic of reframing its radical agenda as the culmination rather than the contradiction of America’s highest ideals.

One cannot but notice that Rufo, a successful activist himself, employs and encourages many of these same tactics. He calls for a “counter-revolution,” which he insists “can be understood as a restoration of the revolution of 1776 over and against the revolution of 1968.” Contrary to the “nihilism” of the Left, Rufo’s revolution is “for…the return of natural right, the Constitution, and the dignity of the individual.” The smell of apple pie and the sound of fireworks seem to emanate from the book’s final pages.

***

But if Rufo’s revolution were to achieve no more than turning back the clock, would history play out any differently than it did last time? Are we reading Rufo the think tank scholar, who analyzes history with disinterested precision? Or are we reading Rufo the activist, who made “critical race theory” a household term and put the academic Left on its heels for the first time in more than half a century?

America’s Cultural Revolution comprises two simultaneous narratives: a historical account and a revolutionary call to arms. Rufo has chronicled the former with such detail that only half has made it into this review. Black militants Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton, Brazilian Marxist Paulo Freire, critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw, even Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (of Obama “Beer Summit” fame) are among the characters who fill out the rest of Rufo’s panorama.

The call to arms, on the other hand, leaves open a question of ends. Like his leftist opponents, Rufo celebrates the prospects of enlisting the working class, which he considers “more anti-revolutionary today than at any time during the upheaval.” Like his opponents, Rufo wraps himself and his agenda in the flag. Like his opponents, he achieves real political results. What will America ideally look like when they are achieved? And how will its new leaders maintain its restored integrity? Readers should pay close attention to what this impressive thinker says. They should pay even closer attention to what he does.