Books Reviewed

Late one night in 556 B.C., King Nabonidus of Babylon saw the gods in a dream. He had just inherited a majestic but precarious birthright: the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers was an object of constant territorial dispute. Some part of it was always under siege, claimed by ancestral inhabitants or trod underfoot by roving warlords. The duty of the Šar Kiššati—the king of the world—was to impose his glorious order upon this chaotic landscape. That daunting assignment now fell to Nabonidus, in whom the gods naturally took an interest.

Turning to them in trepidation, Nabonidus complained of a fearsome menace that had lately disturbed the peace. The umman-manda, the “hordes from who-knows-where,” were stalking like blood-streaked ghosts through his kingdom. In Babylon’s Akkadian language, umman-manda was an all-purpose slur for any foreigner that threatened to destabilize the governing regime. In this case it was being lobbed at the Medes, whose swift horses carried them at alarming speeds from their base camps in the Zagros mountains to whatever city they chose to claim. But Marduk, king of gods, had a surprising revelation for Nabonidus: “That Mede you mentioned—he, his country, and the kings who march at his side shall be no more.” Nabonidus had this story written down on a fired clay cylinder and deposited in Sippar, just north of Babylon. The “Sippar Cylinder” heralds a rival conqueror on the make: Cyrus of Anshan, a Persian, ruler in what is now Iran’s southwestern province of Fars. This unlikely champion would soon bring the proud Median riders low.

Not that Nabonidus should have felt altogether reassured by this news. He may justifiably be suspected of having backdated the prophecy of Cyrus’ victory over the Medes, fabricating ex post facto foreknowledge about a shocking turn of events. But neither Nabonidus nor anyone else could have even pretended to predict what Cyrus would do next. Media was only the beginning: stretching his borders to the western coast of Lydia in modern Turkey, Cyrus ultimately deposed Nabonidus himself to become ruler of Babylon. At its height, the realm Cyrus founded—now known as the Achaemenid Persian empire—covered a breathtaking two million square miles. The sheer scale of his dominion was unheard of. By the time he died in 530 B.C., Cyrus II of Persia, once an obscure disputant in the hinterland dreams of greater kings, had more right than any man before him to be called King of the World.

***

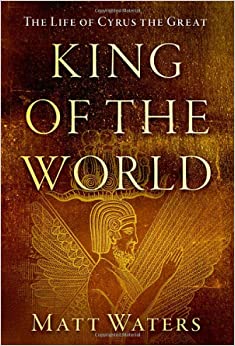

This riveting life story is summarized in Matt Waters’s new biography, King of the World: The Life of Cyrus the Great. A professor of languages and history at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, Waters has been poring meticulously over the surviving documents from ancient Persia for 25 years. His 1997 Ph.D. dissertation was about the Elamites, precursors to the Persians who staged a doomed rebellion against Assyria’s military dictatorship until Assyria crushed them in the 640s B.C. Waters then condensed his study of the Persians’ later expansion into Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire (2014). Now he has put together a careful but readable account of what we know about that empire’s charismatic founder.

It turns out we know more than we used to, and it’s more complicated than it used to be. Only since the 19th century, with the genesis of modern archaeology, has the dust of centuries begun to clear from Babylon and the other great capitals in its vicinity. Among these are the Elamite city of Susa, the Assyrian palaces at Nineveh, and Cyrus’ own lavish royal gardens in his homeland at Pasargadae. The written records that are still emerging from these imposing strongholds—records like the Sippar Cylinder—help reveal how the history of the ancient Near East looked to those who made it.

Before excavations began in earnest, anyone interested in Cyrus or his empire had to content himself more or less with unraveling the cryptic allusions of Hebrew prophets and the reports of Greek historians. The average schoolboy’s picture of the Persian Empire would have been formed, until recently, by what Herodotus of Halicarnassus could gather as he wandered from his birthplace on the western fringes of Persia’s domain. The physician Ctesias of Cnidus also left behind a patchy record of his work in the same region, and the philosopher Xenophon brought back grand tales from his adventures among the mercenary forces of Cyrus’ distant progeny. These writers will always be indispensable: as Waters explains, “we still rely on the Persians’ contemporaries, the ancient Greeks, for narrative material describing what they knew, or thought they knew, about Cyrus.” But the story can now be approached from another angle via the wedge-shaped, i.e., “cuneiform” markings that the scribes of the great kings pressed into brick and clay.

***

Waters does his best to sort through these various testimonials without forgetting the romance and excitement of the story he has to tell. He always shows his hand, laying out the materials he’s working with and explaining how far each of them can be relied upon. This is, as he puts it in a winning act of understatement, “a tricky business, or at least a convoluted one.” The result is not quite as seamless or stylish a narrative as the average reader might hope—those interested in something more polished, though also somewhat more controversial, could turn to Persians (2022) by Cardiff University’s Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones. Waters takes a more circumspect approach. But he makes sure to pause regularly in appreciation of his subject’s awesome grandeur, and those who bear with his many professions of uncertainty will discern the profile of a figure who remains no less captivating for being somewhat enigmatic. Even through the haze of imperfect cultural memory, at a distance of 2,500 years, Cyrus does not fail to dazzle.

His early days were already shrouded in mystery by the time Herodotus started poking around the scene in the later 5th century B.C. Waters suggests this was by design: “Cyrus had an effective publicity machine that worked hard, and was successful, at legitimizing Cyrus within multiple long-standing traditions.” Herodotus was well aware that the monarchy’s public relations team would have been putting in overtime on such a delicate subject as the Great King’s humble beginnings. So he did his best to track down “those Persians who prefer to say how things really are rather than wax reverential about Cyrus” (Histories 1.95). He looked for skeptics whose resentments, or mere indifference, would inoculate them against Cyrus’ cult of personality. This clever tactic put Herodotus well on his way toward the invention of journalism. In the immediate term, though, the best he could do was choose the least fantastical option from among four variant origin stories. The version of events he chose, though perhaps less fawning than the alternatives, was clearly indebted as much to popular mythology as to historical reality. Already in the century after his death, Cyrus’ mystique was such that even his critics were forced to treat his youth as the stuff of legend.

***

The story went that King Astyages of Media dreamed his daughter Mandane drowned all of Asia in her urine. Fearing that her issue would usurp him and rule the continent, Astyages had Mandane married off to a nobody, Cambyses I of the “inferior” Persians—technically a king, but little more in practice than a tribal chieftain. The bad dreams didn’t stop, though. So when Mandane gave birth to Cyrus, Astyages had his trusted subordinate Harpagus carry the child off for summary execution. As Waters wryly observes, “[T]he reader knows where this goes.” Harpagus, apparently discerning what narrative convention required of him, had the child raised in secret by a shepherd. This treachery discovered, Astyages welcomed Cyrus back into his household but punished Harpagus gruesomely, feeding him a supper that turned out to consist of his own murdered offspring. With almost superhuman composure, Harpagus kept quiet—for the time being. He “swallowed…his own anger” along with his children’s flesh, Waters writes. Silently nursing his outrage, Harpagus bided his time.

At this point page-turning mythology overlaps with world-changing history in a compelling fashion. According to the legend, Harpagus signaled covertly to the young Cyrus that should his ambitions outgrow the confines of the Median court, he would find willing allies among those closest to the king. Cyrus, as Waters writes, “did not require much convincing.” What happened next is independently confirmed on a clay tablet from Babylon, containing a text written around the turn of the 5th century B.C. The “Nabonidus Chronicle” states bluntly that “the army of Astyages rebelled, and he was taken prisoner. They delivered him to Cyrus.”

This relatively terse and dispassionate report indicates that Herodotus’ disaffected Persians got at least a few things right. Apparently Cyrus did indeed take advantage of internal discontent to seize control of Media. The Nabonidus Chronicle doesn’t elaborate on his methods. But probably Cyrus presented himself as a competent and likable alternative, if not to governance by forced cannibalism, then at least to a king whose policies had not endeared him to the local nobility.

For the rest of his life, this kind of conquest-by-ingratiation would be Cyrus’ signature technique. It was a stark contrast to previous imperial efforts in the area, which had not been marked by clemency or restraint. The Assyrian monarchs, especially, asserted their dominance over competitors by way of total annihilation. King Ashurbanipal of Assyria kept annals describing, with evident relish, how he salted the earth of his enemies’ lands and defiled their most sacred places. So when the Assyrian capital of Nineveh fell to the Medes and Babylonians in 612, the Jewish prophet Nahum remarked that no one seemed all too broken up about it: “Nineveh is laid waste; who will mourn her?” (Nahum 3:7).

***

In an age when it was not unusual for kings and their courtiers to feast in full view of their enemies’ severed heads, the bar for winning popular support was low. Any conqueror who used force sparingly, rather than gleefully, could hope to be greeted by his new subjects as a liberating hero. This was one of Cyrus’ cardinal strategic insights. Wherever he went, he made efforts to present himself as a gracious administer of justice rather than a vengeful destroyer of worlds. He kept regional customs in place and appointed representatives (satraps) from among the local gentry, leaving their power more or less intact in exchange for fealty.

Scorched earth tactics in the Assyrian mold never vanished from his field manual altogether, though. When the Lydian nobleman Pactyes revolted, Cyrus had him and his supporters hunted down unsparingly, pour encourager les autres. In Waters’s words, this calculated display of force “demonstrated the consequences of rebellion or recalcitrance.” But except in cases of outright insurrection, Cyrus understood that threats of violence would be more effective the more tacit they remained. He preferred to win hearts rather than stop them from beating.

Nowhere was this approach more successful than in Babylon, the crown jewel of both his military and his political career. By the time he marched on the city in 539 B.C., Cyrus’ many campaigns had put him in a position to make a serious bid for total control. If he faltered now, he could lose everything. But if Babylon should kneel before him, who could stand? As it turned out, the city only needed a push. Taking his troops south toward the Tigris River, Cyrus met Babylonian forces at Opis, near modern Baghdad. He won that engagement handily and then, according to the Nabonidus Chronicle, entered Babylon itself “without a battle.” Herodotus describes a more protracted siege, though with the same definitive result. According to his sources, Babylon’s famously vast outer fortifications were so distant from the city center that the downtown crowd could go on “dancing and carousing” in blissful ignorance while Cyrus’ invading armies swept through the far-off gates (Histories 1.191).

***

It’s a fanciful but telling detail. In truth, the dancing and carousing may well have been performed not in ignorance of Cyrus’ entry, but in celebration of it. In his inimitable style, Cyrus saw that a display of peace and reconciliation would make him look like the good guy. Nabonidus was often away from the capital for long stretches of time, pursuing obscure antiquarian interests and even attempting to elevate the moon god Sin at the expense of the imperious Marduk. Betting that the people were uncomfortable with these theological innovations on the part of an absentee king, Cyrus announced that he had come to put the pantheon to rights. In a proclamation called the Cyrus Cylinder, which Waters translates in an appendix, he presented a gauzy picture of himself as the people’s savior from a generation of neglectful and blasphemous leadership. Marduk, out of pity for humanity, “took Cyrus by the hand, the king of Anshan. He summoned his chosen one; he named his name to rule over all.”

It was almost too easy to fill out the details of this triumphal narrative: Nabonidus, the senile madman, was cast into gibbering ignominy by Cyrus, heaven’s chosen one. But though plenty of expert branding was involved, these advertisements for Cyrus’ rule were not pure fiction. As historian Tom Holland writes in his gripping Persian Fire (2007), Cyrus “had shown himself far more sensitive to the alien and complex traditions of Mesopotamia, and to the potential they might offer his regime, than Nabonidus had ever done.” People craved stability. Cyrus knew that if he offered it, a lasting empire could be his in return.

A simple enough observation, but a groundbreaking one with countless potential applications. As Machiavelli noted in The Prince (Chapter 6), Cyrus “owed nothing to fortune except opportunity, which provided material to mold into whatever form seemed best.” Empires in the region tended to fall from within, weakened steadily by infighting until some enterprising invader brought it all crashing down. This had been going on for centuries, but it took a man of Cyrus’ unique genius to see the opportunity it presented—an opportunity not only for military vigor, but also for good governance. “Under Cyrus,” declares the Athenian statesman in Plato’s Laws, “the Persians found the right balance between servitude and freedom” (3.694a-b). Bound to their leader by terms of endearment as well as obligation, his Persian subjects loved and feared him in equal measure. Even the leading lights of Athens, whose forebears had to fight a grueling war of independence against his successors, looked back with appreciation at Cyrus’ industry and wisdom.

***

Because his virtues were fundamental ones, they could win over almost anyone. The Jewish exiles he found living in Babylon—no less than the Greek sojourners at his court—had good cause to admire him. They had been torn from Jerusalem and deported into hateful captivity decades earlier by the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II. “By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept” (Psalm 137): this signal catastrophe was a cruel mockery of the Holy Land and a fearsome indictment, the prophets said, of its leadership class. Still, “the Lord will not nurse his anger forever” (Psalm 103). Since it was Cyrus’ practice to keep traditional customs in place and restore them where broken, he allowed the exiles to return home and rebuild their ruined temple. For this reason the God of the Israelites agreed with Marduk of the Babylonians in one and only one particular: Cyrus was heaven-sent. “Thus says the LORD to his anointed, to Cyrus, whom I have grasped by his right hand,” declares the prophecy of Isaiah: “‘I will go before you, to straighten out the bent and twisted places’” (Isaiah 45:1-2). The word in Hebrew for “his anointed” is “m’shichu,” i.e., “his messiah.” Even if unwittingly, Cyrus became a favored agent of the universe’s one true king.

The respect in which he was held by Athens and Jerusalem alike makes Cyrus an instructive object lesson for our times. It has become fashionable to insinuate that Western historians often distort or ignore the history of the East out of cultural prejudice. Waters himself indulges in a few passing comments along these mistaken lines, blithely indicting “Western historical traditions, with echoes of colonialism.” It’s a shame he vitiates his otherwise expert scholarship with this reflexive over-generalization, since his own research points toward quite a different conclusion. People being what they are, any encounter between two or more cultures is bound to involve some suspicion and outright animosity on all sides. But frequently, as Waters’s book shows, Western researchers have been eager and glad to learn as much as they could about Cyrus.

After all, it’s not as if Herodotus had access to some inconvenient Persian or Babylonian chronicles which he swept under the rug to preserve an appearance of Greek superiority. That would have been entirely out of character. He would have been delighted to get his hands on a transcript of the Cyrus Cylinder, or any of the other precious records that are now emerging from the embattled archaeological sites of the ancient Near East. As more records emerge, it only becomes clearer that Western observers, even when they had incomplete information, could recognize Cyrus’ essential qualities from miles away. Of course he was no classical liberal, and Waters rightly notes that modern efforts to dress him up as some “father of human rights” are sentimental anachronisms. But the virtues he possessed—courage and prudence, a sense of justice and a respect for tradition—are perennial. As some of the West’s best thinkers have powerfully argued, human excellence is objective and universal, though its expressions are as various as the circumstances in which it is displayed. That is why Jews and Greeks alike could see, from their very different standpoints, that Cyrus should be counted among history’s greatest men. We inheritors of the West, two and a half millennia later, can see it too.